Youngsul Shin♦°

A Case Study on Improving Ball Tracking Performance through Error Analysis Based on Data Class Refinement

Abstract: This study addresses performance issues in a legacy golf ball tracker deployed in industrial applications, where recognition failures were long suspected to be caused by environmental factors such as ball color, obstacles, and lighting changes. This study presents a progressive class refinement method to systematically identify these error sources and leverages the findings to build a reliable, deep learning-based tracker. To investigate failures on a data-driven basis, this study employed this refinement method to define various environmental classes and analyze the legacy tracker’s errors within each class. The analysis confirmed that the tracker’s vulnerability was due to its reliance on a limited feature set (e.g., color, size, shape), making it susceptible to real-world variations. Based on the detailed classes derived from this analysis, this study trained a robust Deep Neural Network (DNN) using a comprehensive and well-structured training dataset. The resulting DNN-based tracker demonstrated significantly higher recognition rates and greater robustness across diverse environments compared to the legacy system. These results demonstrate that class refinement and data-driven error analysis significantly contribute to enhancing deep learning model performance.

Keywords: Progressive Class Refinement , Data-Driven Error Localization , Error-Aware Dataset Construction , Performance Enhancement

Ⅰ. Introduction

Accurate and reliable ball tracking technology plays a pivotal role in a wide range of industries, including screen golf and soccer strategy analysis, where it is utilized for diverse purposes such as analyzing player performance and conducting tactical assessments. Users expect sensors to recognize the ball’s movement quickly and accurately, and this trust is directly linked to service satisfaction. However, the legacy ball tracker operated by the organization that requested this study for several years has failed to meet these expectations. Despite being a core asset to the business strategy, the system has been the subject of persistent customer complaints due to sporadic recognition errors in various field-like environments, leading to a decline in business credibility and direct operational difficulties.

However, the fundamental difficulty in problem solving lay in the uncertainty surrounding the legacy ball tracker system. Existing developers could only empirically guess that factors such as the various colors of the ball, surrounding objects like golf clubs or shoes, and external environmental factors like lighting and sunlight were the causes of errors, but they were unable to identify the root cause through engineering principles. As is the reality for many small-sized enterprises, development artifacts such as requirements specifications and design documents for the tracker were non-existent. Furthermore, with the departure of the entire original development team, it was difficult to grasp the requirements of the system and the origin intent of the developers. The source code was heavily reliant on third-party libraries based on complex mathematics, making a precise analysis of its behavior challenging. As the ball tracker system accepted unstructured data as input, analyzing the cause of errors between input and output was even more difficult than for systems that handle structured data.

To find the root cause of the errors in this legacy ball tracker and improve its performance, this study applies a data-driven, systematic approach to performance analysis and enhancement. First, the study employs a technique called progressive class refinement to localize the cause of errors. This is a process that transforms abstract speculation into concrete, data- based evidence by subdividing an image class where an error occurs into more specific subclasses and conducting iterative tests.

Second, to resolve the vulnerabilities identified through the analysis, the study implements a new ball tracker based on a DNN, which is robust to exceptional situations and external noise. For the development of a high-performance DNN, the study strategically utilizes the refined classes defined during the error analysis throughout the model’s training and validation. By paying closer attention to data quality in the specific classes where errors occur, this study enhances the model’s robustness. Furthermore, by measuring performance on a per-class basis during validation, this study presents a framework that allows for a detailed analysis of the model’s strengths and weaknesses in specific situations, moving beyond the ambiguous metric of "average performance", i.e., the fallacy of the average.

The contribution of this study can be summarized as follows:

· Data-driven error analysis method for black-box legacy systems: This study proposes a practical method, ’progressive class refinement’, to systematically identify and specify the failure causes of legacy systems that lack documentation or information.

· Error-aware dataset construction and training strategy: This study presents an intelligent strategy for constructing and utilizing training datasets that leverages the identified error classes to compensate for the DNN model’s vulnerabilities and enhance its robustness.

· Fine-grained performance verification framework: This study proposes a framework that enables a multi-faceted verification of the new system’s reliability by deeply analyzing the model’s performance on a per-class basis, going beyond average accuracy.

· Application in a real-world industrial environment: This study demonstrates the effectiveness of the progressive class refinement approach by applying it to solve a problem in an actual industrial setting.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews existing related work. Section 3 describes the problem statement and the overall approach to solving it. Section 4 performs the error analysis using class refinement, and Section 5 shows the performance improvement based on this refinement. Section 6 discusses the findings of this study. Finally, Section 7 concludes the study.

Ⅱ. Related Work

Traditional pattern recognition algorithms rely on handcrafted features and conventional machine learning techniques, making them computationally efficient and widely adopted in object tracking applications due to their simplicity and real-time performance[1-3]. Despite their computational advantages, the performance of these algorithms heavily depends on the quality of handcrafted features, which may not be optimal for complex and dynamic scenarios encountered in real- world applications[4]. Wang et al. highlighted these limitations in their analysis of automatic composition systems for broadcast sports videos, noting that traditional approaches fail to maintain consistent performance across varying environmental conditions[5]. Huang et al. reported that SURF descriptors fail to provide sufficient discriminative power for small, textureless objects like balls, particularly in cluttered environments[ 6]. The SIFT-based ball tracking system proposed by Ren et al. degraded significantly when dealing with fast-moving objects due to motion blur and insufficient distinctive features on spherical surfaces[ 7].

DNNs utilize sophisticated deep learning architectures such as convolutional neural networks, recurrent neural networks, and transformers that automatically learn features from raw data, eliminating the need for handcrafted features[8]. Vicente-Martínez et al. focused on a semi-supervised network using YOLOv7 and DeepSORT for soccer ball detection and tracking, achieving superior accuracy of 95% compared to traditional methods[9]. Ahmad et al. emphasized the capabilities of DeepSORT as a modern multi-target tracking algorithm that overcomes occlusion and varying illumination conditions that commonly affect traditional tracking systems[10]. Zhang et al. present PCTrack, a novel real-time object tracking system for edge devices that achieves 19.4% to 34.7% accuracy improvements over existing methods to address outdated detections, tracking errors, and missed new objects[11].

Traditional evaluation metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score provide basic performance characterization but often fail to capture the detailed error causes of ball tracking applications[12,13]. Statistical approaches to error analysis have gained prominence in recent years, focusing on probabilistic models of system behavior[14,15]. Hoiem et al. categorized each false positive and false negative into types such as classification error, localization error, confusion with similar object categories, or confusion with background[ 16]. Sophisticated mathematical frameworks enable quantitative prediction of how subsystem uncertainties propagate through vision pipelines[17]. Stereo vision research adopts parametric sensitivity analysis to rank contributors to error[18]. While these methods constitute a data-driven approach for analyzing error causation, they do not provide formal definitions of the input data conditions that generate errors.

The uniformity of training data has emerged as a critical factor affecting the performance and generalizability of deep learning models. Johnson et al. highlighted that effective classification with imbalanced data is an important area of research, as high class imbalance is naturally inherent in many real-world applications[ 19]. Zhang et al. conducted an empirical study examining the joint impact of feature selection and data resampling on imbalanced classification tasks[20]. Their findings demonstrate that the combination of appropriate feature selection with strategic resampling significantly improves model performance on imbalanced datasets. Krawczyk introduced learning from imbalanced data streams using ensemble methods, which has been particularly relevant for online learning scenarios where data distribution may shift over time[21]. Kumar et al. introduced curriculum learning with self-paced learning, allowing models to automatically select training samples based on their current learning state[22]. Zhou et al. proposed the bilateral- branch network for long-tailed learning, which uses separate branches for representation learning and re-balancing[23]. However, these existing methods cannot improve the uniformity of data within subclasses that are defined by an arbitrary dimension of interest.

Ⅲ. Overall Approach

This section presents the problems identified in the legacy ball tracker system and provides a detailed description of the approach adopted in this study to resolve these issues. The proposed approach introduces an error analysis and performance enhancement framework based on the progressive refinement of input data classes.

3.1 Problem Statement

The park golf ball tracker is a critical component that enables virtual park golf in indoor environments. When a player hits a ball with a club, the tracker analyzes its movement to compute a motion vector, which is subsequently used by a park golf simulator to visualize the trajectory of the ball in a virtual space.

This integrated virtual park golf simulation system was commercialized and operational for several years, during which customer complaints consistently emerged regarding inconsistencies between the behavior of the simulated and actual balls. The existing development team hypothesized that the ball tracker within the virtual park golf simulation system was the source of error. The developers were guessing at the cause of the problem solely on the basis of empirical observations. When tasked with investigating this issue, this study encountered two significant constraints: 1) the original development team responsible

for the implementation of the tracking system had left the company, and 2) all technical artifacts necessary to understand the intended functionality of the tracking system, including requirements specifications, design documents, and test reports, were absent. This phenomenon is indeed a realistic problem that many small businesses face.

Despite the lack of formal documentation, systemlevel testing confirmed that the simulator received motion vectors inconsistent with observed physical behavior, definitively localizing the fault to the tracker. However, subsequent manual inspection of the source code did not reveal the specific cause of the erroneous vector calculations.

3.2 Approach based on Data Class Refinement

A notable characteristic of the tracker’s source code was its implementation of traditional pattern recognition techniques using the OpenCV library. Given the mathematical complexity encapsulated in OpenCV and the inherent sensitivity of pattern recognition systems to input variations, this study conjectured that the tracker’s output exhibited significant dependency on input data characteristics. This study therefore adopted a data-driven approach to analyze error causes through the examination of the input-output relationship.

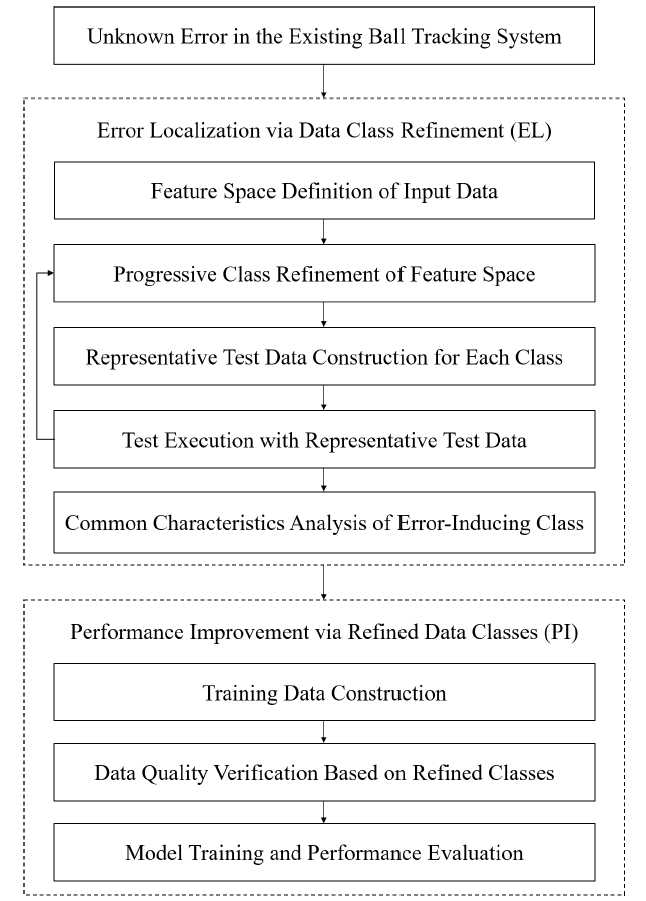

This study proposes a data class refinement-based method for analyzing errors and improving performance in traditional pattern recognition systems. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the approach comprises two primary phases: 1) Error Localization via Data Class Refinement (EL), 2) Performance Improvement via Refined Data Classes (PI). The EL phase progressively refines input data classes to identify common characteristics of error-inducing data through data- driven analysis. The PI phase uses the refined data classes to construct training datasets and evaluate training data quality, thereby facilitating the development of high-performance neural networks.

The objective of the EL phase is to identify common characteristics of input data that cause errors. The EL phase localizes the characteristics of error-inducing input data by dividing the spectrum of input data into classes and iteratively refining these classes. The EL phase comprises the following five steps:

1) Feature Space Definition of Input Data: The input data accepted by the system can be represented as a combination of characteristics that compose it. The ball tracker receives sequential images as input data, and each image’s characteristics can be expressed by the objects within the image and the environment in which the objects are placed.

2) Progressive Class Refinement of Feature Space: Once the entire feature space is defined, the spectrum of values for each characteristic can be divided into multiple classes. Any given class can further be subdivided into subclasses. Refined classes exhibit a hierarchical relationship. The characteristics of a refined subclass inherit the characteristics of the class from which it was refined. Repeating the refinement progressively can lead to the smallest unit of subclass for which further refinement is no longer meaningful.

3) Representative Test Data Construction for Each Class: If data corresponding to a class are not predefined, data belonging to that class must be constructed. If a sufficient quantity of data has been constructed for a refined class, an arbitrary number of samples can be selected from that refined class. Since the selected arbitrary samples belong to the same class, they can be understood as having the same characteristics. The selected samples serve as representative test data for each class.

4) Test Execution with Representative Test Data: The representative test data are fed as input to the system under test, and the corresponding outputs are observed. If an error occurs in the output, the process can be repeated from step 2, "Progressive Class Refinement of Feature Space," to further localize the error characteristics of the output. The decision to repeat this loop is determined by a pre-defined error rate threshold through the test criteria. Classes with an error rate higher than the threshold become candidates for refinement. However, even classes with a very high error rate might not undergo further refinement if they are understood to be the core cause of the error occurrence.

5) Common Characteristics Analysis of Error- Inducing Data: By analyzing the common characteristics of error-inducing data within classes where refinement has been stopped due to sufficiently high error rates, the characteristics of inputs that the system under error analysis cannot handle are identified in a data-driven manner, rather than relying on developers’ intuition.

The PI phase aims to improve the performance of an existing system with errors, utilizing the refined data classes defined in the EL phase. The PI phase consists of the following three steps:

1) Training Data Construction: To improve the performance of the existing system, it is necessary to construct data required for DNN training. A common strategy for building DNN training data is to build as large a dataset as possible to ensure high performance of the selected DNN model.

2) Data Quality Verification Based on Refined Classes: Even if a large amount of data is constructed in the previous step, a large quantity of data does not necessarily represent the quality of the training data. High-quality training data must satisfy both sufficient quantity and uniform distribution across the input data spectrum. The uniformity of training data is assessed based on the refined data classes defined in the EL phase. Classes with insufficient training data can be identified using the number of data belonging to the refined classes.

3) Model Training and Performance Evaluation: This step involves evaluating the performance of the trained model. Performance evaluation can also be conducted for each refined class. Performance evaluation based on refined classes is a method that allows for a detailed observation of model performance without falling into the fallacy of the average.

Ⅳ. Error Localization via Class Refinement

This section localizes the errors in the legacy ball tracker system provided for this case study using the class refinement method. The spectrum of input data is progressively divided into finer subclasses through class refinement, and by iterating this process, the source of errors is formally identified and described.

4.1 Foundational Definitions

An input image I is modeled as a set comprising the objects ball, club head, shoe, and human head, denoted as

Each object is characterized by distinct features, defined as follows:

where:

· [TeX:] $$c_x \in \mathbb{R}^3$$: the average color of the region in HSV color space,

· [TeX:] $$s_X \in \mathbb{R}^{+}$$: the area of the region in pixels,

· [TeX:] $$\kappa_x \in[0,1]$$: circularity, computed as [TeX:] $$\kappa_x=\frac{4 \pi s_x}{p_x^2},$$

· [TeX:] $$\iota_x \in[0,1]$$: a binary indicator of localized illumination,

· [TeX:] $$\alpha_x \in \mathbb{R}^{+}$$: the estimated absolute luminance.

The ball tracker function T takes an input image I and returns a set of detected objects:

In an error-free case, [TeX:] $$O_{\text {detected }}$$ contains only the actual ball object B or is an empty set [TeX:] $$\emptyset$$ if no ball is present. The internal behavior of the function T consists of two functions as follows:

1) Color filter M: This function applies a mask based on predefined ball color range [TeX:] $$C_{\text {ball}}^{\text {ref }} .$$ For an object x with observed color [TeX:] $$\phi_{\text {color }}(x), \text { if } \phi_{\text {color }}(x)$$ is within the range, M(x) = 1; otherwise, M(x) = 0. The observed color [TeX:] $$\phi_{\text {color }}(\text{x})$$ is a function of the object’s intrinsic color [TeX:] $$c_x,$$ and the external light conditions [TeX:] $$\iota_x \text { and } \alpha_x .$$ The color filter M is defined as:

2) Geometric filter R: After converting the masked result to grayscale, this function R evaluates the observed size [TeX:] $$\phi_{\text {size}}(x)$$ and observed circularity [TeX:] $$\phi_{\text {circul}}(x)$$ of an object x against a predefined ball size range [TeX:] $$\text { Sre } S_{\text {ball }}^{\text {ref }}$$ and circularity [TeX:] $$G_{\text {circul }}^{\text {ref }}.$$ If they match, R(x) = 1; otherwise, R(x) = 0. The geometric filter R is defined as:

3) Finally, an object x is recognized as a ball if and only if [TeX:] $$x \in O_{\text {detected }} \Longleftrightarrow R(x / M(x)=1)=1 .$$

Let E denote the error function. E (I) = 1 if the ball tracker produces an error, and E (I) = 0 otherwise. The primary error is false positive, where a non-ball object, (e.g., club head Cl, shoe Sh, human head H u) is identified as a ball. Thus, if [TeX:] $$x \in\{C l, S h, H u\} \text{ and } x \in T(I), \text{ then } E(I) = 1.$$

4.2 Progressive Class Refinement

To identify the sources of errors in the legacy ball tracker, this study incrementally performed class refinements. This subsection corresponds to steps 1 through 4 of the five detailed steps of the EL phase, as shown in Fig. 1.

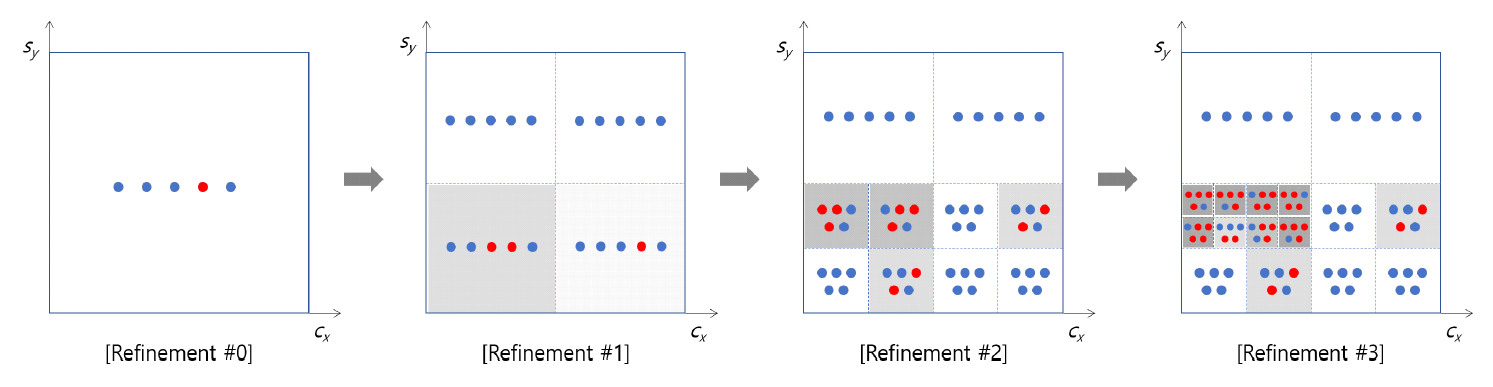

An example of the progressive refinement process for data classes is illustrated in Fig. 2. For the sake of simplicity, this study assumes a two-dimensional feature space. The horizontal and vertical axes, cx and sx , denote the color and size values of an object x, respectively. The blue dots represent data that do not induce errors, while the red dots represent those that induce errors.

On the coordinate plane, each rectangular region containing the dots constitutes a data class. The gray shade of each region indicates the error rate of the corresponding subclass; a darker shade signifies a higher error rate. The initial refinement stage consists of a single class that encompasses the entire feature space. As the refinement process continues, the feature space is partitioned into multiple subclasses. It can be observed that this gradually reveals subclasses characterized by higher error rates and smaller, more specific regions within the feature space.

Let [TeX:] $$\Gamma^{(0)}$$ denote the initial set of classes that covers the entire feature space [TeX:] $$\mathscr{F},$$ such that:

A class [TeX:] $$\Gamma_i$$ is a subset of the entire feature space [TeX:] $$\mathscr{F},$$ defined by a specific range of feature values. Formally, an instance [TeX:] $$I \in \mathscr{F}$$ belongs to a class [TeX:] $$\Gamma_i$$ if its feature values lie within prescribed intervals:

The progressive refinement process is as follows:

1) At iteration k, start with the current set of classes [TeX:] $$\Gamma^{(k)}=\left\{\Gamma_1^{(k)}, \Gamma_2^{(k)}, \ldots, \Gamma_N^{(k)}\right\}$$

2) For each class [TeX:] $$\Gamma_j^{(k)} \in \Gamma^{(k)},$$ select a representative image dataset [TeX:] $$D_j^{(k)} \subset \Gamma_j^{(k)} .$$

3) For each image [TeX:] $$I \in D_j^{(k)},$$ run the tracker T(I) and evaluate the error E(I).

4) Calculate the error rate for class [TeX:] $$\Gamma_j^{(k)}:$$

5) If ErrRate [TeX:] $$\left(\Gamma_j^{(k)}\right) \gt \theta_{e r r}$$ (a predefined error threshold) and the class [TeX:] $$\Gamma_j^{(k)}$$ is not yet granular enough, refine [TeX:] $$\Gamma_j^{(k)}$$ into a set of mutually exclusive subclasses [TeX:] $$\Gamma_{j, 1}^{(k+1)}, \Gamma_{j, 2}^{(k+1)}, \ldots, \Gamma_{j, m}^{(k+1)} .$$ This refinement is done by partitioning one or more feature dimensions.

6) The new set of classes for the next iteration, [TeX:] $$\Gamma^{(k+1)},$$ is formed by the unrefined classes and the newly created subclasses.

7) This process terminates when it is determined that the classes of interest have been sufficiently refined.

4.3 Analysis of Identified Error-Inducing Classes

Upon completion of the process of progressive class refinement, this study obtains a set of refined, high-error-rate classes, denoted as [TeX:] $$\Omega_{e r r}^{\text {final }}=\left\{\Omega_1^*, \Omega_2^*,\ldots, \Omega_M^*\right\}$$ Each element [TeX:] $$\Omega_q^*$$ in this set is a collection of images for which the ball tracker consistently fails in a similar manner. The subsequent analytical stage involves formally defining the error characteristics for each of these classes.

The objective of this stage is to conduct a datadriven investigation to extract a formal set of conditions, [TeX:] $$\Phi q,$$ that accurately describes the common properties of [TeX:] $$\forall I \in \Omega_q^* .$$ This set [TeX:] $$\Phi q$$ serves as the formal explanation for the tracker’s failure in that specific scenario. For each given error class [TeX:] $$\Omega_q^*,$$ this identification process involves a statistical analysis of the feature distributions of its constituent images. This study analyzes the distributions of the misidentified object’s features as well as the external light conditions.

The outcome of this analytical process is the formal definition of the property set [TeX:] $$\Phi q$$. This set is designed to serve as a robust descriptor for the class, such that the properties of [TeX:] $$\forall I \in \Omega_q^*$$ satisfy the conditions in [TeX:] $$\Phi q$$. Formally, the process for each [TeX:] $$\Omega_q^*$$ is to find a set of conditions [TeX:] $$\Phi q$$.

such that:

[TeX:] $$\forall I \in \Omega_q^*,$$ the properties of I are consistent with [TeX:] $$\Phi q$$.

Once the set of characteristics [TeX:] $$\Phi q$$ is identified, it provides a data-driven explanation for the tracker’s failure. The conditions specified in [TeX:] $$\Phi q$$ create the precise circumstances under which a non-ball object x satisfies the tracker’s detection logic, [TeX:] $$T(I)=O_{\text {detected }}= \{x\}$$, by causing its observed color and/or circularity to fall within the target reference ranges.

It is essential to reiterate that this characterization is performed independently for each class [TeX:] $$\Omega_q^*$$ The final result is a portfolio of distinct error scenarios, [TeX:] $$\left\{\Phi_1,\right.\left.\Phi_2, \ldots, \Phi_M\right\}$$ where each [TeX:] $$\Phi q$$ explains a specific and unique vulnerability of the ball tracker.

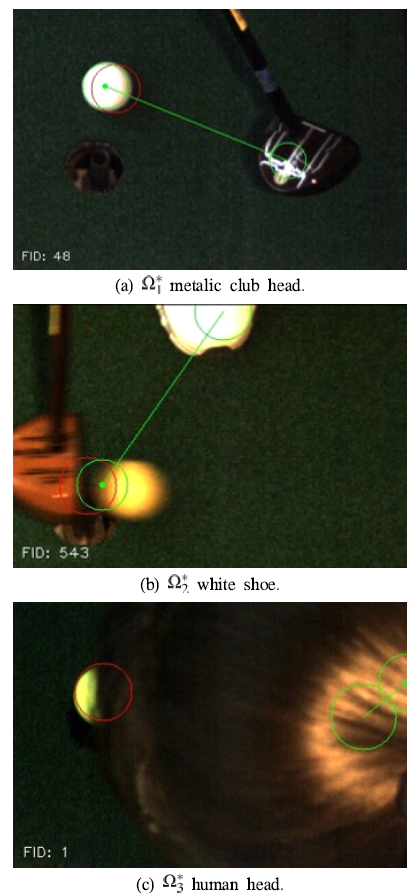

Through this analytical process, this study successfully identified and characterized a portfolio of distinct, high-error-rate classes. After several iterations of refinement, the process terminated, yielding a set of 3 final error-inducing classes [TeX:] $$\Omega_{\text {err }}^{\text {final }}$$ with error rates exceeding the predefined threshold of [TeX:] $$\theta_{\text {err }}=0.8 .$$ Table 1 presents a selection of the most significant error classes, detailing their defining characteristics ([TeX:] $$\Phi_q$$) and the specific conditions that lead to false positives.

Fig. 3 shows example images of the error-inducing classes presented in Table 1. In the images, the red circle indicates the initial position of the object recognized as a ball, and the two green circles represent two positions when the object recognized as a ball moves. The vector connecting the centers of these two green circles is calculated as the ball’s motion vector. Fig. 3a shows a metallic club head being recognized as a ball. Fig. 3b shows a shoe being recognized as a ball. Fig. 3c shows a person’s head reflected by light being recognized as a ball.

Fig. 3.

The non-ball objects of interest-the club head, shoe, and human head-are characterized by diverse feature spaces. Under normal circumstances, their intrinsic properties, such as color, size, and circularity, do not align with the reference parameters the ball tracker uses for ball identification. Consequently, these objects are not expected to be classified as balls.

The analysis of these identified classes provides a clear, data-driven explanation for the legacy tracker’s sporadic failures. Each class represents a distinct scenario where a non-ball object’s features are misinterpreted by the tracker’s rigid filtering logic.

The analysis reveals that under specific environmental conditions, the observed features of these objects can be significantly distorted, leading to false positives. The primary cause of this distortion is the influence of external illumination, particularly localized illumination ([TeX:] $$\iota_x$$) and absolute luminance ([TeX:] $$\alpha_x$$). For instance, while an object’s intrinsic color may be dissimilar to that of a ball, high luminance can cause its observed color, [TeX:] $$\phi_{\text {color}}(x),$$ to shift into the reference range [TeX:] $$\mathscr{C}_{\text {ball }}^{\text {ref }} .$$ This mechanism explains how objects that are fundamentally different from a ball are erroneously recognized by the legacy system. Due to the sensitivity of pattern recognition-based ball tracking to external light variations, this study concluded that deep learning-based ball tracking technology is required.

Table 1.

| Class ID | Description | Key Characteristics ([TeX:] $$\Phi_{\mathrm{q}}$$) | False Positive Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| [TeX:] $$\Omega_1^*$$ | Reflective or metallic club head under bright and direct luminance at address. | [TeX:] $$\iota_{\mathrm{x}}=1$$ (localized illumination), [TeX:] $$150\lt \alpha_{\mathrm{x}}\lt 200 \mathrm{~cd} / \mathrm{m}^2$$ (high luminance), [TeX:] $$0.58\lt \hat{\delta}\left(c_x, C_{\text {hall }}^{\text {ref }}\right) \lt 0.7$$ (low color similarity), [TeX:] $$0.74 \lt \hat{\delta}\left(s_x, s_{\text {hall }}^{\text {ref }}\right) \lt 0.79$$ (middle size similarity), [TeX:] $$0.7\lt \kappa_{\mathrm{x}}\lt 0.82$$ (middle circularity). | 92% |

| [TeX:] $$\Omega_2^*$$ | White shoe with rounded front, partially visible in the frame. | [TeX:] $$\iota_{\mathrm{x}}$$ (don’t care), [TeX:] $$85\lt \alpha_{\mathrm{x}}\lt 120 \mathrm{~cd} /m2$$ (high luminance), [TeX:] $$0.42\lt \hat{\delta}\left(c_x, C_{\text {hall }}^{\text {ref }}\right) \lt 0.5$$ (low color similarity), [TeX:] $$0.91 \lt \hat{\delta}\left(s_x, s_{\text {hall }}^{\text {ref }}\right) \lt 0.98$$ (high size similarity), [TeX:] $$0.5\lt \kappa_{\mathrm{x}}\lt 0.6$$ (low circularity). | 85% |

| [TeX:] $$\Omega_3^*$$ | Top of a human head moving through the camera’s field of view. | [TeX:] $$\iota_{\mathrm{x}}$$ (don’t care), [TeX:] $$40\lt \alpha_{\mathrm{x}}\lt 50 \mathrm{~cd} /m2$$ (low luminance), [TeX:] $$0.51\lt \hat{\delta}\left(c_x, C_{\text {hall }}^{\text {ref }}\right) \lt 0.65$$ (low color similarity), [TeX:] $$0.8 \lt \hat{\delta}\left(s_x, s_{\text {hall }}^{\text {ref }}\right) \lt 0.92$$ (high size similarity), [TeX:] $$0.6\lt \kappa_{\mathrm{x}}\lt 0.8$$ (middle circularity). | 81% |

Ⅴ. Performance Improvement via The Refined Classes

In this section, this study develops and evaluates the performance of a YOLO-based ball tracking system trained on an error-aware dataset constructed using the refined data classes identified in Section 4.

5.1 Error-Aware Dataset Construction via The Refined Data Classes

To overcome the limitations of the legacy ball tracking system, this study implemented a deep learning approach using YOLO-based architectures. The key innovation in this section lies in the systematic construction of the training dataset, which directly leverages the error-inducing classes identified through the progressive refinement process. The refined classes revealed that errors in the legacy system were concentrated in specific and well-defined scenarios. Based on this insight from the refined classes, this study developed a strategy for collecting training data with specific features.

The dataset construction followed these principles:

· Error-aware-based sampling: For each refined error class [TeX:] $$\Omega_q^*,$$ this study systematically collected training samples that exhibited the characteristic conditions [TeX:] $$\Phi_q.$$ This ensured that the YOLO models would be exposed to the specific scenarios where the legacy system failed.

· Balanced representation: To prevent bias in the learned model, this study ensured equal representation across all the identified classes. This balanced approach prevents the model from overfitting to any particular error scenario while maintaining robust performance across diverse conditions.

· Normal operation coverage: In addition to errorinducing scenarios, this study included samples from normal operational conditions where the legacy system performed correctly. This ensures the YOLO models maintain high performance in standard scenarios while improving on problematic cases.

In the progressive class refinement process, 132 classes were defined. A data pool of 115,500 training samples were subsequently collected, averaging 875 samples per class. The data pool comprises 112,844 normal samples (97.7% of total) and 2,656 abnormal samples representing critical error classes (2.3% of total).

All images were annotated using the CVAT[24]. A team of four trained annotators performed the labelng, and a two-stage verification process was implemented to ensure high-quality, consistent annotations across the entire dataset. Due to the proprietary nature of the data collected from commercially operating screen park golf booths, this study are unable to make the dataset publicly available but have strived to transparently report the proposed method.

5.2 Model Training and Evaluation

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed erroraware method, this study conducted a comprehensive comparative analysis.

This study implemented two distinct dataset construction strategies: a generic approach and the proposed error-aware approach. Both strategies draw from the same initial data pool and result in training, validation, and test sets of identical sizes to ensure fair and direct comparison.

5.2.1 Test Set

To ensure unbiased final evaluation, a test set was isolated from the total pool before any training commenced as follows:

· Split ratio: 10% of the total data pool.

· Sampling method: Stratified random sampling to maintain the original distribution of normal and abnormal data.

· Final test set composition:

- Total size: 11,550 images.

- Normal images: 11,284.

- Abnormal images: 266.

This test set is identical for all experiments and was not exposed to any model during the training or validation phases.

5.2.2 Generic Training and Validation Sets

This approach simulates a standard development process where the developer has no prior knowledge of the specific error-inducing data classes. The principle underlying this strategy is to form training and validation sets through random sampling from the available pool as follows:

· Validation set (10%): 11,550 images are randomly sampled from the 103,950-image pool.

· Training set (80%): The remaining 92,400 images are used for training.

The abnormal data proportion in this training dataset will be similar to the overall pool ratio, approximately 2.3% (2,390 / 103,950). The expected number of abnormal samples in the training set is approximately 2,124 (92,400 ᅲ 2,390 / 103,950). This dataset construction approach represents a realistic "naive" data construction method commonly used in practice. On average, approximately 266 critical abnormal samples (2,390 - 2,124) are likely to be excluded from the training process, potentially limiting the model’s exposure to important failure cases.

5.2.3 Error-aware Training and Validation Sets

This approach strategically leverages the insights gained from the error analysis to ensure the model learns from its most critical weaknesses. The dataset is deliberately constructed to guarantee that all known failure cases are used for training, thereby maximizing the model’s exposure to critical data as follows:

· Validation set (10%): To achieve this principle, the 11,550-image validation set is randomly sampled exclusively from the normal images in the pool.

· Training set (80%): The 92,400-image training set is composed of:

- All 2,390 abnormal images from the pool.

- The remaining 90,010 images, randomly sampled from the normal images.

This strategy guarantees that the model is trained on every identified failure case, directly targeting the system’s vulnerabilities for improvement.

5.2.4 Models and Training Configuration

Considering real-time performance, accuracy, computational complexity, industrial application cases, and deployment feasibility, this study selected YOLOv5l and YOLOv7 as the experimental object detection models. Both models demonstrate excellent balance among real-time performance, accuracy, and computational complexity[25,26]. However, the YOLOv5 series has relatively more industrial deployment cases and offers greater ease of deployment[25,26].

The performance is compared against five key benchmarks:

· Legacy system: The original ball tracker based on pattern recognition.

· Baseline YOLOv5l: A standard YOLOv5l model trained on a generic dataset.

· Proposed YOLOv5l: A more advanced YOLOv5l model trained using the error-aware dataset.

· Baseline YOLOv7: A standard YOLOv7 model trained on a generic dataset.

· Proposed YOLOv7: A more advanced YOLOv7 model trained using the error-aware dataset.

All DNN models were trained on an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. Training parameters were optimized for industrial ball tracking requirements:

· Training epochs: 300 epochs with early stopping (patience=50).

· Batch size: 32 images per batch.

· Learning rate: Initial learning rate of 0.01 with cosine annealing.

· Image size: 384×384 pixels to maintain real-time performance.

· Optimizer: SGD with momentum=0.937 and weight decay=0.0005.

5.2.5 Performance on Error-Inducing Classes

This study evaluated the performance specifically on the three critical error-inducing classes [TeX:] $$\Omega_1^*, \Omega_2^*$$ and [TeX:] $$\Omega_3^*$$. Table 2 presents the false positive rate for each system. While the baseline DNN models show a significant improvement over the legacy system, they still struggle with these specific, challenging scenarios, exhibiting false positive rates between 15.2% and 25.1%. In contrast, the models trained with the proposed error-aware approach demonstrate a dramatic reduction in these errors. For the metalic club head error class [TeX:] $$\Omega_1^*,$$ the proposed YOLOv5l reduces the false positive rate from the baseline’s 18.5% down to just 2.1%. This proves that the performance gain is not merely from using a DNN, but from the strategic way the DNN is trained.

Table 2.

| Error Class | False Positive Rate (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legacy System | YOLOv5l | YOLOv7 | |||

| Generic | Error-Aware | Generic | Error-Aware | ||

| [TeX:] $$\Omega_1^*$$ (Metalic club head) | 92.0 | 18.5 | 2.1 | 15.2 | 1.9 |

| [TeX:] $$\Omega_2^*$$ (White shoe) | 85.0 | 21.8 | 3.2 | 17.5 | 2.8 |

| [TeX:] $$\Omega_3^*$$ (Human head) | 81.0 | 25.1 | 1.8 | 21.3 | 1.5 |

This substantial improvement is not limited to YOLOv5l. When the error-aware approach is applied to the YOLOv7 architecture, it similarly slashes the false positive rate from the baseline’s 15.2% to 1.9%. These results demonstrate the potential for broad applicability of the error-aware dataset construction method and its capability to enhance the robustness of diverse model architectures.

5.2.6 Overall System Performance

Beyond the specific error classes, this study evaluated the overall system performance across all the refined classes. This study evaluated the overall performance of the models. Table 3 presents the comprehensive metrics. The baseline YOLOv5l achieves a respectable F1-score of 0.915. However, the proposed YOLOv5l raises this score to 0.980, primarily by improving recall and significantly reducing the overall false positive rate from 6.8% to 1.2%. This demonstrates that the proposed error-aware approach successfully corrects the model’s key weaknesses in the critical error-inducing classes [TeX:] $$\Omega_1^*, \Omega_2^*$$ and [TeX:] $$\Omega_3^*$$ without compromising its general performance.

Table 3.

| Metric | Legacy System | Baseline YOLOv5l | Proposed YOLOv5l | Baseline YOLOv7 | Proposed YOLOv7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 0.743 | 0.921 | 0.975 | 0.942 | 0.985 |

| Recall | 0.896 | 0.909 | 0.986 | 0.934 | 0.991 |

| F1-score | 0.812 | 0.915 | 0.980 | 0.938 | 0.988 |

| mAP@0.95 | 0.683 | 0.854 | 0.958 | 0.891 | 0.965 |

| False Positive Rate | 18.3% | 6.8% | 1.2% | 5.1% | 1.0% |

| Inference Time (ms) | 12.5 | 38.7 | 38.7 | 29.5 | 29.5 |

Furthermore, the comparison with YOLOv7 confirms the proposed error-aware approach’s value. While the Baseline YOLOv7 is inherently more powerful than the Baseline YOLOv5l with F1-scores of 0.938 versus 0.915, the error-aware approach elevates its performance even further, achieving a final F1-score of 0.988. The consistent performance gap between the baseline and proposed models across both architectures shows that the error-aware training strategy, not just the choice of a newer model, is the primary driver of the enhanced robustness and reliability.

Ⅵ. Discussion

The experimental results presented in Section 5 offer substantial evidence for the efficacy of the proposed approach. This section provides an interpretation of these results, discusses the broader implications of the method, and addresses its generalizability.

6.1 Granular Analysis of Performance on Critical Error Classes

This study shows that strategically constructed training datasets significantly outperform generically assembled datasets, especially in handling critical error cases. The comparison between the generic baseline model and the proposed error-aware model highlights this clearly. The generic dataset represents a typical development scenario in which developers lack prior knowledge of specific failure cases, thus randomly distributing critical error samples between training and validation sets. Consequently, some critical error cases inevitably remain unseen by the model during training, leaving it susceptible to predictable failures.

In contrast, the error-aware dataset, informed by detailed error analysis via progressive class refinement, strategically incorporates all identified critical error scenarios into the training set. This intentional approach ensures maximum exposure to the most challenging data points, effectively reducing the false positive rates in specific error classes [TeX:] $$\Omega_1^*, \Omega_2^*$$ and [TeX:] $$\Omega_3^*$$. While the baseline models trained on generic datasets exhibit substantial improvement over the legacy system, their performance on these abnormal classes remains notably limited. However, the error-aware models dramatically reduced the false positive rates from between 15.2%-25.1% down to below 3.2%, underscoring the need for targeted training strategies.

These findings expose the fallacy of relying solely on overall average accuracy metrics, which mask significant deficiencies in model performance on critical, though infrequent, scenarios. These findings expose the fallacy of relying solely on overall average accuracy metrics, which mask significant deficiencies in model performance on critical, though infrequent, scenarios. True model performance, particularly in real- world applications, is better reflected by metrics specifically tailored to challenging cases. Thus, the approach advocates a shift in focus from general accuracy to targeted error reduction, thereby enhancing practical robustness and user trust in AI systems.

6.2 Generalizability

The core contribution of this study is not the application of a specific YOLO model, but rather the establishment of a systematic approach for diagnosing and correcting failures in black-box vision systems. This approach is generalizable and consists of two key stages.

First, the progressive class refinement process acts as a data-driven method for reverse-engineering a system’s implicit requirements. It transforms vague developer assumptions into a formal specification of failure modes, called error-inducing classes. This process is analogous to creating a requirement document written in the language of data, making it universally applicable to any vision system regardless of its underlying architecture.

Second, the error-aware dataset construction leverages these findings to guide the training process intelligently. This study’s philosophy is rooted in quality and focus over sheer quantity. While a dataset of 2,656 abnormal images, representing 2.3% of the total data pool, might seem small in the context of deep learning, these are not just random samples. They are the most valuable data points, each representing a confirmed failure case. By strategically ensuring these samples are included in the training set, this study forces the models to confront and learn from their most critical weaknesses. The performance gap between the baseline and proposed models, trained on identical-sized datasets, demonstrates the effectiveness of this strategic approach.

The proposed approach holds substantial promise beyond ball tracking. It can be easily adapted to diverse industrial domains experiencing unexplained errors in legacy vision systems. For instance, in medical imaging, the approach could systematically identify subtle but critical image conditions causing diagnostic AI systems to fail in detecting specific pathologies. Similarly, in manufacturing, it can pinpoint precise conditions leading to incorrect quality control decisions, thereby improving the overall reliability of the system.

6.3 Limitations and Future Directions

While the proposed approach achieved significant improvements, several limitations warrant discussion. Understanding these constraints is essential for contextualizing the contribution of this study and identifying directions for future research.

The current implementation of progressive class refinement relies on manual analysis to identify and characterize error patterns. This process requires domain expertise and significant human effort to examine failure cases and define class boundaries. Automating this process through clustering algorithms or anomaly detection could reduce human effort and enable broader adoption.

Additionally, the proposed framework assumes relatively stable error patterns over time. In practice, environmental conditions and error characteristics may evolve due to seasonal changes, equipment aging, or facility modifications. Dynamic environments where error characteristics shift rapidly may require online learning extensions to the methodology, enabling continuous adaptation to emerging error patterns.

Ⅶ. Conclusion

The progressive class refinement method successfully identified and characterized the root causes of errors in the legacy ball tracker system, revealing that the failures were not random but concentrated in specific and well-defined scenarios. This data-driven approach to error analysis provides a systematic framework that can be generalized beyond ball tracking applications.

The findings reveal that environmental factors, particularly illumination conditions, play a more significant role in system failures than previously recognized. The formal characterization of error conditions provides actionable insights for system designers.

The error-aware dataset construction strategy based on the refined classes enabled the evaluation of data quality and facilitated the construction of a high-quality training dataset. By systematically sampling errorinducing scenarios identified through progressive refinement, this study ensures that the deep learning model receives sufficient exposure to edge cases that would otherwise be underrepresented. This targeted approach proved more effective than traditional data augmentation techniques, as evidenced by the model’s robust performance across all identified error classes.

This study makes four significant contributions to the field of industrial computer vision and systematic performance improvement:

1) Progressive class refinement: Unlike traditional debugging methods that rely on manual inspection or ad-hoc testing, the progressive refinement process provides a novel systematic method for identifying and characterizing error patterns through iterative data subdivision. This method is generalizable to other computer vision applications that require systematic error identification and resolution.

2) Formal error characterization framework: The mathematical formalization of error conditions through characteristic sets provides a rigorous foundation for understanding system failures. This framework enables:

· Precise documentation of failure modes.

· Reproducible error analysis across different systems.

· Systematic validation of proposed solutions.

3) Error-aware dataset construction strategy: This study demonstrates that leveraging the results of the error analysis for the construction of training data significantly improves the performance of the deep learning model. This approach addresses a critical gap in the machine learning pipeline by establishing the connection between error analysis and dataset design. The results show that balanced representation across error classes is more important than overall dataset size for addressing specific system vulnerabilities.

4) Generalizable framework for legacy system improvement: Beyond the specific application to ball tracking, this study provides a template for modernizing legacy industrial vision systems. The combination of systematic error analysis, targeted data collection, and deep learning deployment offers a cost-effective path for organizations seeking to improve existing systems without complete replacement.

Future research directions encompass developing automated tools for error pattern discovery and characterization, and researching transfer learning strategies for applying error patterns across similar industrial applications.

Biography

References

- 1 V. Pallavi, J. Mukherjee, A. K. Majumdar, and S. Sural, "Graph-based multiplayer detection and tracking in broadcast soccer videos," IEEE Trans. Multimedia, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 794-805, 2008. (https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2008.922869)doi:[[[10.1109/TMM.2008.922869]]]

- 2 G. Chen, W. Lian, F. Hu, et al., "Research on intelligent target recognition method based on pattern recognition and deep learning," in Second Target Recognition and Artificial Intell. Summit Forum, vol. 11427, T. Wang, T. Chai, H. Fan, and Q. Yu, Eds., Int. Soc. Opt. Photon. SPIE, 2020. (https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2550783)doi:[[[10.1117/12.2550783]]]

- 3 E. Musaoõlu and v. C. N. Öztürk ve, "Comparison of object tracking methods and performance analysis of kernelized correlation filter with different appearance models," in 2021 29th Signal Process. and Commun. Appl. Conf. (SIU), pp. 1-4, 2021. (https://doi.org/10.1109/SIU53274.2021.947794 9)doi:[[[10.1109/SIU53274.2021.9477949]]]

- 4 Y. Ji, P. Yin, X. Sun, K. Hawari Hawari Bin Ghazali, and N. Guo, "A comparative study and simulation of object tracking algorithms," in Proc. 2020 4th ICVIP, pp. 161-167, Xi’an, China, 2021, ISBN: 9781450389075. (https://doi.org/10.1145/3447450.3447476)doi:[[[10.1145/3447450.3447476]]]

- 5 Y. Dong, J. Zhang, X. Chang, and J. Zhao, "Automatic sports video genre categorization for broadcast videos," in 2012 Visual Commun. and Image Process., pp. 1-5, 2012. (https://doi.org/10.1109/VCIP.2012.6410850)doi:[[[10.1109/VCIP.2012.6410850]]]

- 6 C.-L. Huang, H.-C. Shih, and C.-Y. Chao, "Semantic analysis of soccer video using dynamic bayesian network," IEEE Trans. Multimedia, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 749-760, 2006. (https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2006.876289)doi:[[[10.1109/TMM.2006.876289]]]

- 7 J. Ren, J. Orwell, G. A. Jones, and M. Xu, "Real-time modeling of 3-D soccer ball trajectories from multiple fixed cameras," IEEE Trans. Circuits and Syst. for Video Technol., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 350-362, 2008. (https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2008.918276)doi:[[[10.1109/TCSVT.2008.918276]]]

- 8 Y.-C. Huang, I.-N. Liao, C.-H. Chen, T.-U. İk, and W.-C. Peng, "TrackNet: A deep learning net work for tracking high-speed and tiny objects in sports applications," arXiv preprintcustom:[[[-]]]

- 9 J. Vicente-Martínez, M. Márquez-Olivera, A. Garcia, and V. Hernandez, "Adaptation of yolov7 and yolov7_tiny for soccer-ball multidetection with deepsort for tracking by semisupervised system," Sensors, vol. 23, p. 8693, Oct. 2023. (https://doi.org/10.3390/s23218693)doi:[[[10.3390/s23218693]]]

- 10 F. Ahmad, A. Chauhan, and P. Singh, "Multi object tracking system form video streaming using yolo," in 2023 4th IEEE GCAT, pp. 1-6, 2023. (https://doi.org/10.1109/GCAT59970.2023.103 53400)doi:[[[10.1109/GCAT59970.2023.10353400]]]

- 11 X. Zhang, H. Xu, C. Yu, and G. Tan, "Pctrack: Accurate object tracking for live video analytics on resource-constrained edge devices," IEEE Trans. Circuits and Syst. for Video Technol., vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 3969-3982, 2025. (https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2024.3523204)doi:[[[10.1109/TCSVT.2024.3523204]]]

- 12 K. Bernardin and R. Stiefelhagen, "Evaluating multiple object tracking performance: The clear mot metrics," J. Image Video Process., vol. 2008, Jan. 2008, ISSN: 1687-5176. (https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/246309)doi:[[[10.1155/2008/246309]]]

- 13 J. Luiten, A. Osep, P. Dendorfer, et al., "Hota: A higher order metric for evaluating multi-object tracking," Int. J. Comput. Vision, vol. 129, no. 2, pp. 548-578, Feb. 2021, ISSN: 0920-5691. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-020-01375-2)doi:[[[10.1007/s11263-020-01375-2]]]

- 14 C. Guo, G. Pleiss, Y. Sun, and K. Q. Weinberger, "On calibration of modern neural networks," in Proc. 34th ICML’17, vol. 70, pp. 1321-1330, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2017.custom:[[[-]]]

- 15 Y. Ovadia, E. Fertig, J. Ren, et al., "Can you trust your model’s uncertainty? evaluating predictive uncertainty under dataset shift," in Proc. 33rd Int. Conf. NIPS, NY, USA, 2019.custom:[[[-]]]

- 16 D. Hoiem, Y. Chodpathumwan, and Q. Dai, "Diagnosing error in object detectors," in Proc. 12th ECCV 2012, vol. Part III, pp. 340-353, Florence, Italy, 2012, ISBN: 978-3-642-33711-6. (https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-33712-3_25)doi:[[[10.1007/978-3-642-33712-3_25]]]

- 17 H. Huang, J. Liu, S. Liu, P. Jin, T. Wu, and T. Zhang, "Error analysis of a stereovision-based tube measurement system," Measurement, vol. 157, p. 107659, 2020, ISSN: 0263-2241. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.10 7659)doi:[[[10.1016/j.measurement.2020.107659]]]

- 18 M. Yang, Y. Qiu, X. Wang, J. Gu, and P. Xiao, "System structural error analysis in binocular vision measurement systems," J. Marine Sci. and Eng., vol. 12, no. 9, 2024, ISSN: 2077-1312. (https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12091610)doi:[[[10.3390/jmse12091610]]]

- 19 J. Johnson and T. Khoshgoftaar, "Survey on deep learning with class imbalance," J. Big Data, vol. 6, p. 27, Mar. 2019. (https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0192-5)doi:[[[10.1186/s40537-019-0192-5]]]

- 20 C. Zhang, P. Soda, J. Bi, et al., "An empirical study on the joint impact of feature selection and data resampling on imbalance classification," Applied Intell., vol. 53, no. 5, pp. 5449-5461, Jun. 2022, ISSN: 0924-669X. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-022-03772-1)doi:[[[10.1007/s10489-022-03772-1]]]

- 21 B. Krawczyk, "Learning from imbalanced data: Open challenges and future directions," Progress in Artificial Intell., vol. 5, Apr. 2016. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s13748-016-0094-0)doi:[[[10.1007/s13748-016-0094-0]]]

- 22 M. P. Kumar, B. Packer, and D. Koller, "Selfpaced learning for latent variable models," in Proc. 24th Int. Conf. NIPS’10, vol. 1, pp. 1189-1197, Vancouver, Canada, 2010.custom:[[[-]]]

- 23 B. Zhou, Q. Cui, X.-S. Wei, and Z.-M. Chen, "BBN: Bilateral-branch network with cumulative learning for long-tailed visual recognition," in 2020 IEEE/CVF Conf. CVPR, pp. 9716-9725, 2020. (https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.0097 4)doi:[[[10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00974]]]

- 24 OpenVINO Toolkit Team, CVAT: Computer Vision Annotation Tool, https://www.cvat.ai/, Accessed: 2025-01-06, 2025.custom:[[[https://www.cvat.ai/,Accessed:2025-01-06,2025]]]

- 25 O. E. Olorunshola, M. E. Irhebhude, and A. E. Evwiekpaefe, "A comparative study of yolov5 and yolov7 object detection algorithms," J. Computing and Soc. Inf., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1-12, Feb. 2023. (https://doi.org/10.33736/jcsi.5070.2023)doi:[[[10.33736/jcsi.5070.2023]]]

- 26 Ultralytics, Ultralytics models documentation, https://docs.ultralytics.com/ko/models/, Accessed: 2025-01-27, 2025.custom:[[[https://docs.ultralytics.com/ko/models/,Accessed:2025-01-27,2025]]]