Sangwoo Choi♦ , Minsik Kim* and Daeyoung Park°

Joint Design of Receive Beamforming and RIS Configuration for Over-the-Air Computation

Abstract: This work addresses the minimization of mean-squared error (MSE) in an over-the-air system aided by reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RIS). By jointly optimizing the receive beamforming vector at the base station and the reflection coefficients of the RIS, we aim to improve the accuracy of signal ag- gregation under device power constraints. We depart from conventional uniform-forcing methods by in- troducing a misalignment-allowed optimization (Miso) framework that improves performance. Simulations show the proposed algorithms reduce MSE sig- nificantly compared to prior methods.

Keywords: Over-the-air computation , beamforming optimization , MSE minimization , reconfigurable intelligent surface

Ⅰ . Introduction

Over-the-air computation (AirComp) has emerged as an efficient way for aggregating signals in wireless multiple-access channels (MAC) by exploiting their superposition property. However, additive noise and channel fading amplify aggregation errors and reduce the accuracy of the computed sum. Miso methods solve for the BS receive beamforming vector and device transmit scaling factors via iterative updates, yielding a low-complexity algorithm[1] that outperforms traditional uniform-forcing methods.

Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces have been proposed as an energy-efficient approach for reshaping the wireless propagation environment through programmable phase shifts on passive elements. By dynamically directing incoming waves, RIS can enhance desired signal paths, mitigate interference, and adjust phase offsets before the combined signals reach the receiver. When integrated with AirComp, RIS-assisted reflection provides a promising method to further minimize the mean-squared error in over-the-air data aggregation. However, jointly optimizing the base station’s receive beamformer and the RIS’s unit-modulus phase coefficients presents a complex nonconvex problem.

This paper proposes an equivalent reformulation that separates the beamforming vector and the phase shift vector design, facilitating an iterative algorithm that maintains global optimality while addressing practical constraints on power and phase shifts. Unlike prior AirComp methods based on uniform-forcing[2], we adopt a Miso optimization approach[3] and further extend it to support RIS-based configurations.

Ⅱ . System Model

Let [TeX:] $$\mathbf{h}_k \in \mathbb{C}^N$$ be the direct channel from the k-th device to the base station (BS). Suppose the channel vector from the RIS to the BS is [TeX:] $$\mathbf{R} \in \mathbb{C}^{N \times M}$$ and the channel vector from the k -th device to the RIS is [TeX:] $$\mathbf{t}_k \in \mathbb{C}^M$$. The RIS phase shift vector is [TeX:] $$\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in \mathrm{CM}$$, where each element satisfies [TeX:] $$\left|\alpha_m\right|=1$$. As a result, the effective channel from device k to the BS is

(1)

[TeX:] $$\tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k=\mathbf{h}_k+\mathbf{R} \operatorname{diag}(\alpha) \mathbf{t}_k .$$We denote by bk the transmit scaling factor at the k-th device, and let [TeX:] $$\mathbf{b}=\left[\begin{array}{llll}b_1, & b_2, & \ldots, & b_K\end{array}\right]^{\mathrm{T}}$$ satisfy the constraint [TeX:] $$\left|b_k\right|^2 \leq P_{\max }$$ for all k. When all K devices simultaneously transmit xk with these scaling factors, the signal received at the BS is [TeX:] $$\mathbf{y}=\sum_{k=1}^K \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k b_k x_k+\mathbf{n}$$, where n is additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) distributed as [TeX:] $$\mathbf{n} \sim \mathscr{C} \mathscr{N}\left(\mathbf{0}, \sigma^2 \mathbf{I}\right)$$. We define the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) by [TeX:] $$P_{\max } / \sigma^2$$.

In the averaging framework, the BS aims to compute the average [TeX:] $$\frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K x_k$$ from the received signal y. A receive beamforming vector [TeX:] $$\mathbf{a} \in \mathbb{C}^N$$ is employed at the BS so that

(2)

[TeX:] $$\frac{1}{K} \mathbf{a}^H \mathbf{y}=\frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K \mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k b_k x_k+\frac{1}{K} \mathbf{a}^H \mathbf{n}$$We evaluate the mean-squared error (MSE) between [TeX:] $$\frac{1}{K} \mathbf{a}^H \mathbf{y}$$ and the true average [TeX:] $$\frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K x_k$$

(3)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \mathrm{MSE} & =\mathbb{E}\left[\left|\frac{1}{K} \mathbf{a}^H \mathbf{y}-\frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K x_k\right|^2\right] \\ & =\frac{1}{K^2} \sum_{k=1}^K\left|\mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k b_k-1\right|^2+\frac{\sigma^2}{K^2}\|\mathbf{a}\|^2 . \end{aligned}$$The joint design problem aims to minimize this MSE under per-device power limits and RIS unit-modulus constraints:

(4)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \text { (P1) } \min _{\mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b}, \alpha} & \sum_{k=1}^K\left|\mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k b_k-1\right|^2+\sigma^2\|\mathbf{a}\|^2 \\ \text { s.t. } & \left|b_k\right|^2 \leq P_{\max }, \forall k \\ & \left|\alpha_m\right|^2=1, m \in \mathscr{M} \equiv\{1,2, \cdots M\} . \end{aligned}$$Ⅲ. Proposed Algorithms

To simplify Problem (P1), we first express the optimal bk in terms of a and [TeX:] $$\tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k$$. The optimal bk is given by[1]

(5)

[TeX:] $$b_k=\left\{\begin{array}{cl} \frac{1}{\mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k}, & \text { if }\left|\mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k\right|^2 \geq 1 / P_{\max } \\ \frac{\sqrt{P_{\max }}\left(\mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k\right)^*}{\left|\mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k\right|}, & \text { if }\left|\mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k\right|^2\lt1 / P_{\max } \end{array} .\right.$$Therefore, we have [TeX:] $$\mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k b_k=\min \left(\sqrt{P_{\max }}\left|\tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k^H \mathbf{a}\right|, 1\right)$$, [TeX:] $$\forall k$$. We define [TeX:] $$s_k=\min \left(\sqrt{P_{\max }}\left|\mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k\right|, 1\right)$$, [TeX:] $$s_k \approx 1$$ indicates that device k can fully meet the gain requirement for exact alignment in Over-the-Air computation, and sk > 1 indicates that [TeX:] $$\sqrt{P_{\max }}\left|\mathbf{a}^H \tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k\right|$$ cannot reach 1 under the power constraint. Substituting sk into Problem (P1) yields the following equivalent formulation:

(6)

[TeX:] $$\begin{gathered} \text { (P2) } \min _{\mathbf{a}, \alpha, \mathbf{s}} \sum_{k=1}^K\left(s_k-1\right)^2+\sigma^2\|\mathbf{a}\|^2 \\ \text { s.t. } s_k=\min \left(\sqrt{P_{\max }}\left|\tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k^H \mathbf{a}\right|, 1\right), \forall k \\ \left|\alpha_m\right|^2=1, m \in \mathscr{M} . \end{gathered}$$The optimal solution a to Problem (P2) is also the optimal solution to Problem (P1). We consider a more relaxed problem

(7)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \text { (P3) } \min _{\mathbf{a}, \alpha, \mathbf{s}} & \sum_{k=1}^K\left(s_k-1\right)^2+\sigma^2\|\mathbf{a}\|^2 \\ \text { s.t. } & s_k^2 \leq P_{\max }\left|\tilde{\mathbf{h}}_k^H \mathbf{a}\right|^2, \forall k \\ & \left|\alpha_m\right|^2=1, m \in \mathscr{M} . \end{aligned}$$Note that a feasible (a, s) in Problem (P2) is also feasible in Problem (P3). Thus, the optimal value of Problem (P2) is lower-bounded by Problem (P3). However, the optimal solution to Problem (P3) is also the optimal solution to Problem (P2).

3.1 Optimizing a for Fixed α

When α is fixed, each device’s channel is fixed as well. We optimize a for fixed α. We may use the algorithms in[[1,3].

3.2 Optimizing a for Fixed a

With a fixed a, we rewrite [TeX:] $$\left|\left(\mathbf{h}_k+\mathbf{R} \operatorname{diag}(\alpha) \mathbf{t}_k\right)^H \mathbf{a}\right|^2$$

(8)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \left|\left(\mathbf{h}_k+\mathbf{R} \operatorname{diag}(\alpha) \mathbf{t}_k\right)^H \mathbf{a}\right|^2 & =\left|\mathbf{a}^H \mathbf{h}_k+\mathbf{a}^H \mathbf{R} \operatorname{diag}(\alpha) \mathbf{t}_k\right|^2 \\ & =\left|c_k+\mathbf{d}_k^H \alpha\right|^2, \end{aligned}$$where [TeX:] $$c_k=\mathbf{a}^H \mathbf{h}_k$$ and [TeX:] $$\mathbf{d}_k=\operatorname{diag}\left(\mathbf{t}_k\right)^H \mathbf{R}^H \mathbf{a}$$. The optimization of α under [TeX:] $$\left|\alpha_m\right|=1$$ is then governed by

(9)

[TeX:] $$\begin{gathered} \text { (P4) } \min _{\alpha, \mathbf{s}} \sum_{k=1}^K\left(s_k-1\right)^2 \\ \text { s.t. } s_k^2 \leq P_{\max }\left|c_k+\mathbf{d}_k^H \alpha\right|^2, \forall k \\ \left|\alpha_m\right|^2=1, m \in \mathscr{M} \end{gathered}$$Since [TeX:] $$\left|c_k+\mathbf{d}_k^H \alpha\right|^2$$ is nonconvex in α , we employ an iterative approach. At each step, we linearize [TeX:] $$\left|c_k+\mathbf{d}_k^H \alpha\right|^2$$ around the current α(l), replacing it with a convex lower bound and solving the resulting convex program. From [TeX:] $$|b|^2 \geq-|a|^2+2 \operatorname{Re}\left\{a^* b\right\}$$ for [TeX:] $$a, b \in \mathbb{C}$$, where [TeX:] $$a=c_k+\mathbf{d}_k^H \alpha^{(l)}$$, [TeX:] $$b=c_k+\mathbf{d}_k^H \alpha$$, we have

(10)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} & \left|c_k+\mathbf{d}_k^H \alpha\right|^2 \\ & \geq-\left|c_k+\mathbf{d}_k^H \alpha^{(l)}\right|^2+2 \operatorname{Re}\left\{\left(c_k+\mathbf{d}_k^H \alpha^{(l)}\right)^*\left(c_k+\mathbf{d}_k^H \alpha\right)\right\} \\ & \equiv \hat{\varphi}_k\left(\alpha ; \alpha^{(l)}\right), \end{aligned}$$where α(l)is the l-th iterative estimate of α. Then, the iterative optimization problem is

(11)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \text { (P5) }\left(\alpha^{(l+1)}, \mathbf{s}^{(l+1)}\right)=\arg \min _{\alpha, \mathbf{s}} & \sum_{k=1}^K\left(s_k-1\right)^2 \\ \text { s.t. } & s_k^2 \leq P_{\max } \hat{\varphi}_k\left(\alpha ; \alpha^{(l)}\right), \forall k \\ & \left|\alpha_m\right|^2=1, m \in \mathscr{M} . \end{aligned}$$Since Problem (P5) is a convex problem, we solve it with the interior point method using the CVX toolbox, which is called RIS-Miso-CVX. Since its complexity O ( N3 + M3), we propose low-complexity algorithm based on the projected subgradient method, called RIS-Miso-Subgradient

(12)

[TeX:] $$Repeat $$ \begin{aligned} & v_m \leftarrow\left|[\mathbf{D}]_{m,:} \Lambda\left(\mathbf{D}^H \alpha^{(l)}+\mathbf{c}\right)\right|, \forall m \\ & \alpha \leftarrow \operatorname{diag}(v)^{-1} \mathbf{D} \Lambda\left(\mathbf{D}^H \alpha^{(l)}+\mathbf{c}\right) \\ & s_k \leftarrow \frac{1}{1+\lambda_k}, \forall k \\ & \lambda_k \leftarrow \max \left\{0, \lambda_k+\delta_j\left(s_k^2-P_{\max } \hat{\varphi}_k\left(\alpha ; \alpha^{(l)}\right)\right)\right\}, \forall k \\ & j \leftarrow j+1 \end{aligned} $$ Until convergence$$where [TeX:] $$\mathbf{c}=\left[c_1 \cdots c_K\right]^T \in \mathbb{C}^K$$ and [TeX:] $$\mathbf{D}=\left[\mathbf{d}_1 \cdots \mathbf{d}_K\right] \in$$ [TeX:] $$\mathbb{C}^{M \times K}$$. We obtain [TeX:] $$v_m=\left|[\mathbf{D}]_{m,:} \Lambda\left(\mathbf{D}^H \alpha^{(l)}+\mathbf{c}\right)\right|$$, [TeX:] $$\forall m$$, where [TeX:] $$[\mathbf{D}]_{m,:} \in \mathbb{C}^{1 \times K}$$ is the m-th row of D.

Ⅳ. Numerical results

In this section, we present the RIS-aided AirComp system consisting of Kdevices with a single antenna, an RIS with Mphase shifts, and a BS with Nantennas. We adopt the Rician channel model. To account for obstacles between BS and edge devices, we set the Rician factor to be 0 for the BS device channel and to be 3 for all other channels. We set other parameters as follows: N= 10, P/σ2 = 40dB, and = 10-3.

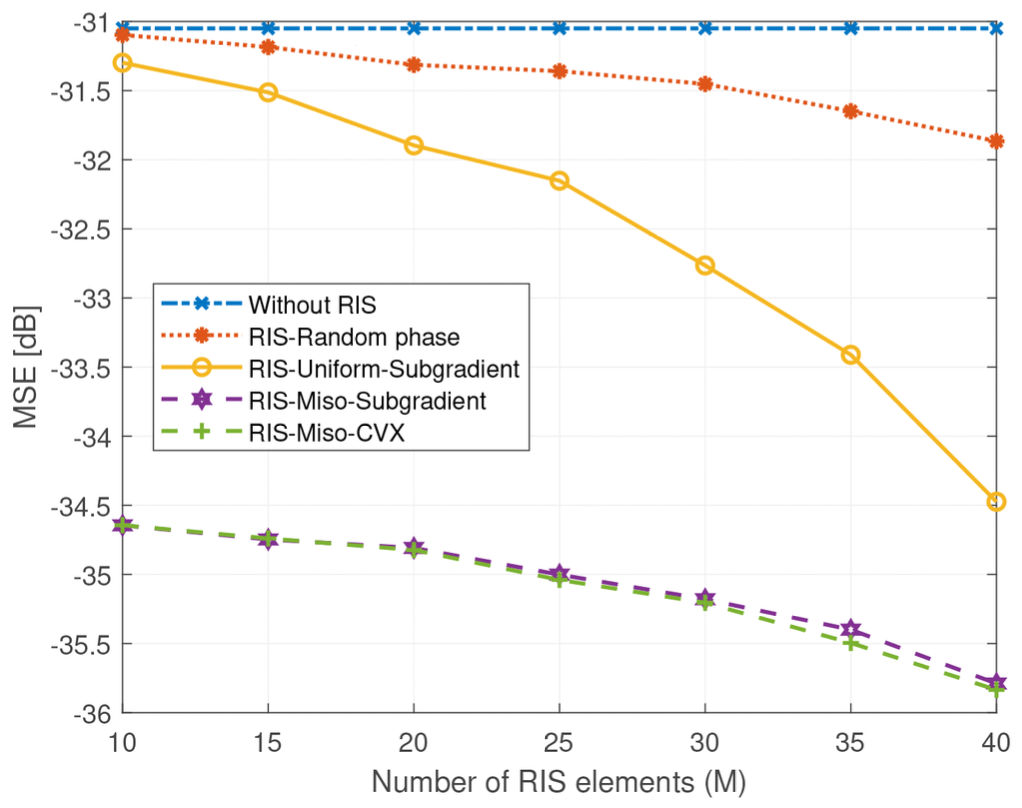

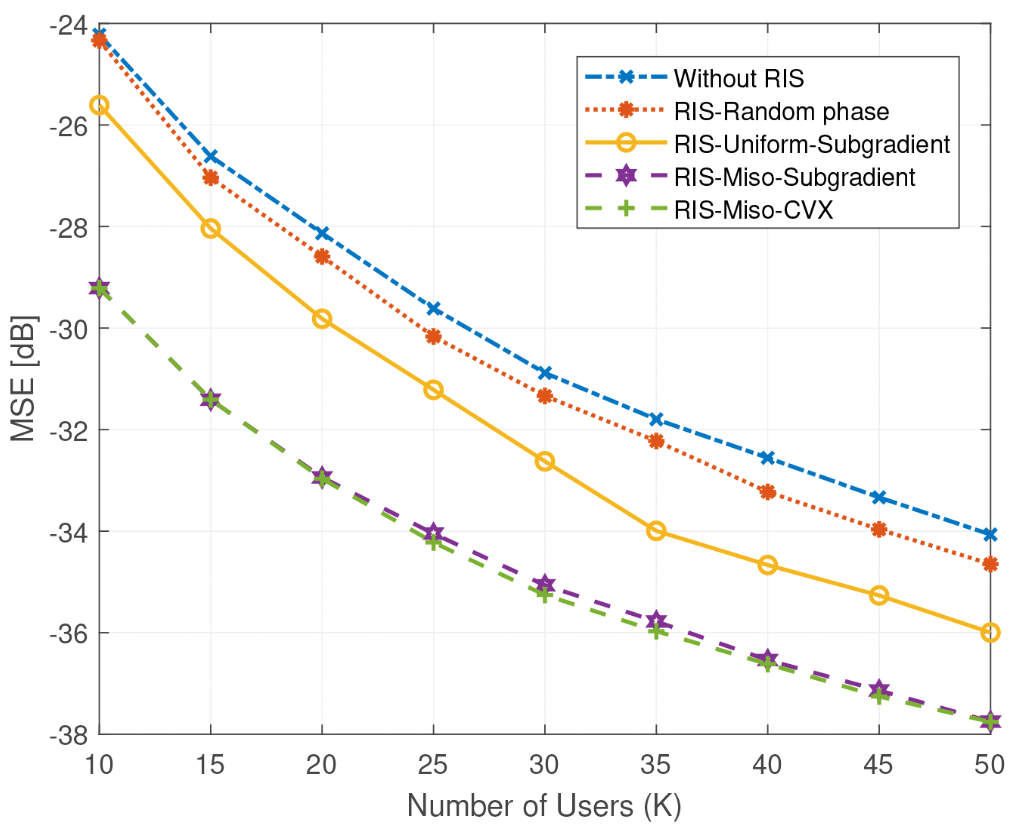

We consider the following schemes for performance benchmarks, ‘Without RIS’, ‘RIS-Random phase’, ‘RIS-Uniform-Subgradient’[2]. ‘RIS-Miso-CVX’ and ‘RIS-Miso-Subgradient’ are our proposed algorithms.

Fig. 1 shows the MSE performance as a function of the number of RIS elements M . As M increases, all RIS-aided methods benefit from enhanced channel alignment, while the baselines (‘RIS-Random Phase’ and ‘Without RIS’) show limited improvement. Among the tested schemes, RIS-Miso-CVX consistently achieves the lowest MSE, serving as the optimal benchmark. RIS-Miso-Subgradient closely tracks the CVX performance, with an MSE gap of only 0.1 dB at M = 35. This confirms that the subgradient method can effectively approximate the optimal solution with significantly lower complexity.

Fig. 2 shows the MSE performance as the number of users Kincreases from 10 to 50, with the number of RIS elements fixed at M = 30. Interestingly, the MSE decreases across all methods as the number of users increases. RIS-Miso-CVX continues to deliver the best performance, while RIS-Miso-Subgradient tracks it closely, with a small gap of only 0.2 to 0.4dB across the full range of K. This confirms the effectiveness of the proposed subgradient method in multiple-user.

Ⅴ. Conclusion

In this letter, we address the MSE minimization in RIS-enhanced over-the-air systems. We decouple the BS’s nonconvex beamforming design and the RIS’s phase shift vector design. We then proposed an iterative approach that alternates between optimizing the receive beamforming vector and updating the RIS’s phase shifting vector, ensuring significant reductions in the aggregation error. Numerical evaluations demonstrated that our methods outperform existing techniques in terms of MSE, particularly when using a large number of RIS elements or users. These findings high-light the value of joint beamforming and RIS configuration in AirComp, opening avenues for future research on advanced, low-complexity algorithms and robust designs capable of handling more diverse and dynamic wireless environments. Furthermore, when applied to federated learning, the proposed algorithms are expected to achieve superior performance compared to other existing methods.

References

- 1 S. Choi, M. Kim, and D. Park, "Optimal beamforming in over-the-air federated learning for efficient model aggregation," to appear in ICT Express.custom:[[[-]]]

- 2 M. Kim and D. Park, "Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces-aided federated learning in over-the-air computation," IEEE Wireless Commun. Lett., vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 1983-1987, Jul. 2024.custom:[[[-]]]

- 3 S. Tang, C. Zhang, J. Li, and S. Obana, "Miso: Misalignment allowed optimization for multiantenna over-the-air computation," IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 2561-2571, Jan. 2024. Fig. 2. MSE under different numbers of users (M = 30).custom:[[[-]]]