IndexFiguresTables |

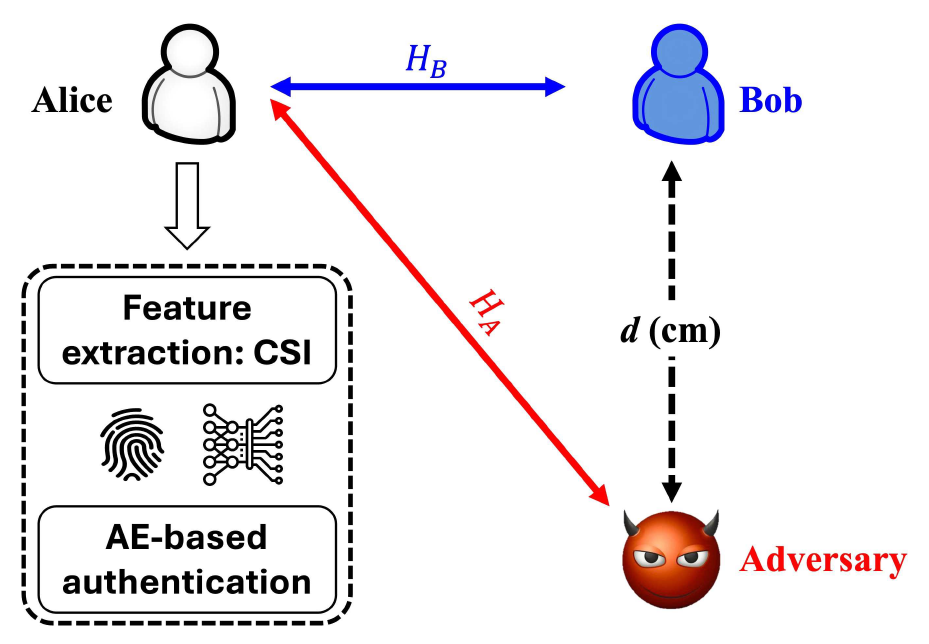

Ralph Kumah Assan , Jihwan Moon , Taehoon Kim and Inkyu BangPhysical Layer Authentication for Mobile Devices in WLAN Systems: An Autoencoder-Based ApproachAbstract: Physical layer authentication (PLA) enhances wireless security by using wireless channel features like channel state information (CSI) to authenticate transmitters and detect adversaries. While machine learning (ML) has been applied to improve PLA, most methods require adversary data or assume a stationary environment, limiting real-world practicality. This paper proposes an autoencoder-based PLA framework that relies solely on legitimate users’ CSI to distinguish them from adversaries in dynamic wireless environments. Using a wireless local area network (WLAN) testbed (e.g., Wi-Fi) with mobile and stationary devices in both line-of-sight (LoS) and non-line-of-sight (NLoS) scenarios, experimental results show that the proposed method outperforms existing schemes in authentication accuracy under mobility conditions Keywords: Physical layer authentication , autoencoder , mobility , channel state information , anomaly detection Ⅰ. IntroductionThe rapid advancement of the fifth-generation (5G) and next-generation wireless networks has unraveled a new era of global connectivity. The evolution of wireless communication systems is expected to provide diverse services and applications through seamless connectivity with various Internet of Things (IoT) devices[1]. The number of IoT devices in wireless networks has increased steadily but they are also exposed to unexpected security threats due to diverse attack vectors in IoT networks. Traditional security protocols in wireless networks primarily depend on cryptographic techniques, which are often inadequate for resource- constrained IoT applications such as sensing and smart home applications[2]. Accordingly, alternative security techniques such as physical layer security and physical layer authentication (PLA) have been recently studied to compensate for limitations in directly applying the existing security protocols to IoT devices[3]. Physical layer authentication (PLA) is one of the promising techniques for enhancing wireless security, which exploits features of wireless channels, such as channel state information (CSI), to authenticate legitimate transmitters and identify malicious users (i.e., adversaries)[4]. Recent studies have shown that machine learning (ML)-based PLA schemes can improve authentication accuracy[5]. For example, Liu et al. applied support vector machine (SVM) algorithms to PLA, using CSI to build user-specific profiles in stationary scenarios[6]. However, most of the existing ML-based PLA techniques are required to collect both legitimate users’ and adversaries’ CSI data for training. In fact, it is difficult to measure adversaries’ CSI data in practical scenarios, and thus there have been studies to tackle this issue. In [7], this problem is investigated by focusing on a stationary environment. This study employs the one-class SVM (OSVM) model which is trained exclusively on legitimate users’ data. The OSVM model shows high accuracy in detecting anomalies considering static conditions. In addition, the use of generative adversarial networks (GAN) was employed in [8]-[10] to detect adversaries while also identifying legitimate radio frequency transmitters in stationary environments. In [11], a dual-input convolution neural network (CNN) model is proposed to learn the temporal and spatial similarity scores between two input CSIs limited by the need for both legitimate user and adversary CSI data, making them less suitable for real-world use. Despite the growing body of work on ML-based PLA schemes, most existing studies focus on stationary environments or require adversary data, which makes them unsuitable for mobile settings. Moreover, deep learning-based classifiers such as CNNs, LSTMs, or transformers, though effective, typically depend on supervised learning involving both classes of data, including adversarial samples, which are often unavailable in real-time deployment scenarios. In contrast, autoencoder architectures offer a powerful solution for one-class learning by learning compact representations of legitimate users’ CSI only, and identifying deviations as anomalies. This makes them naturally aligned with practical PLA systems where only legitimate channel profiles can be reliably acquired. Furthermore, the autoencoder can flexibly capture complex spatio-temporal patterns without explicit attacker labels, thus eliminating the dependency on a complete adversarial dataset and improving robustness under mobility. To fill this gap, we propose an autoencoder-based PLA framework that only exploits legitimate users’ CSI data to efficiently learn the temporal and spatial differences between legitimate users and adversaries in dynamic wireless environments.While our experiments are limited to a controlled indoor Wi-Fi 6 testbed using the 2.4 GHz band, the methodology is generalizable and can be extended to other configurations including outdoor, 5 GHz Wi-Fi, or mmWave systems in future work. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows: (1) We propose an autoencoder-based anomaly detection algorithm to authenticate legitimate users against adversaries in mobile environments; (2) We set up our testbed considering mobile and stationary devices in the wireless local area network (WLAN) environment (e.g., Wi-Fi) and collect extensive CSI data for training and evaluation in both line-of-sight (LoS) and non line-of-sight (NLoS) scenarios; (3) The experiment results demonstrate that the proposed PLA scheme outperforms the OSVM-based method, particularly in dynamic wireless environments, highlighting its potential for real-world IoT security applications. A comparison with the OSVM serves as a meaningful baseline aligned with the constraint of unsupervised learning, and further evaluations with other deep models are suggested as future extensions. Ⅱ. System and Threat ModelIn this section, we introduce our system and threat model, including some basics for the IEEE 802.11 physical layer and assumptions for an adversary. 2.1 System ModelWe consider two legitimate devices (Alice and Bob) and a single adversary as illustrated in Fig. 1, where [TeX:] $$H_B \text { and } H_A$$ indicate channel state information in the frequency domain at Bob and adversary, respectively. Alice (e.g., access point) is responsible for authenticating legitimate users (i.e., Bob) considering CSI as a feature for a one-class classifier. We assume that both Bob and an adversary are mobile and apart from each other at least d cm. We consider that every node (including an adversary) adopts orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) for physical layer transmission with the IEEE 802.11ax standard[12]. Alice receives OFDM signals from Bob or the adversary and estimates the CSI of them. The received signal at Alice in the frequency domain is given by

where k denotes a subcarrier index, H(k), X(k), and N(k) indicates channel response in the frequency domain, transmitted symbol, and additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN), respectively, on subcarrier k Although our setup considers only one legitimate transmitter-receiver pair and one adversary, this model can be extended to multi-user scenarios involving concurrent transmissions and interference sources. In such environments, the classifier may need to be adapted to operate over segmented or aggregated CSI streams from multiple users, and future work will explore such scalability. The IEEE 802.11ax standard adopts the high-efficiency long training field (HE-LTF) to precisely estimate CSI over wideband. If we consider X(k) as the pilot symbol in the frequency domain, the channel estimation on subcarrier k is calculated as

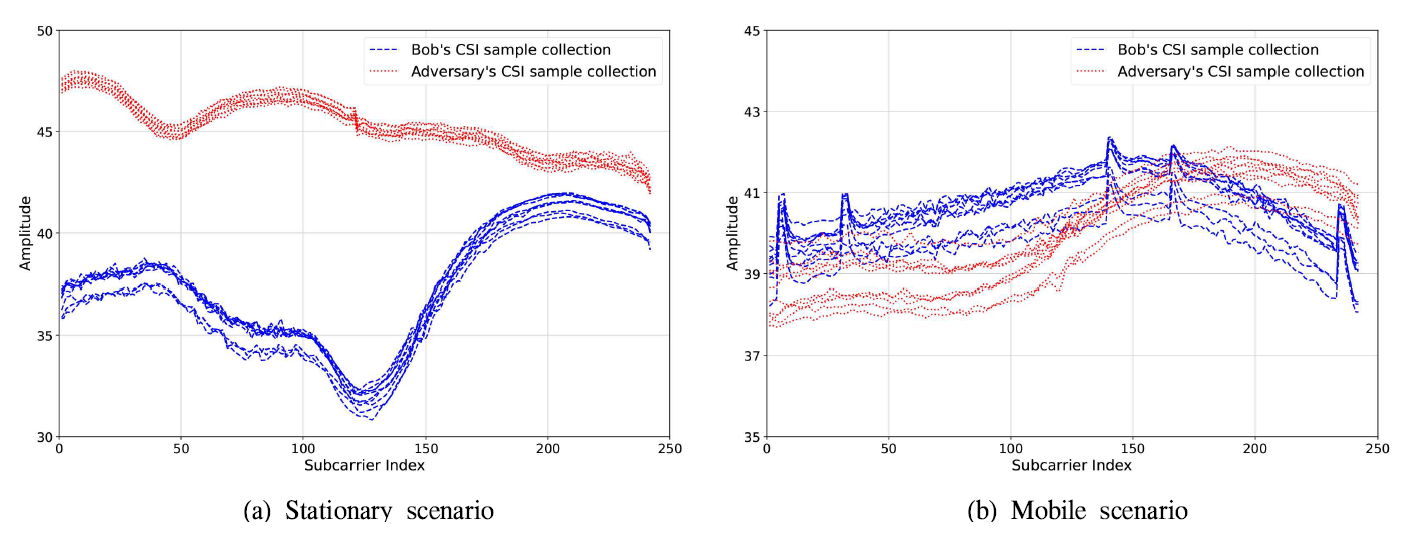

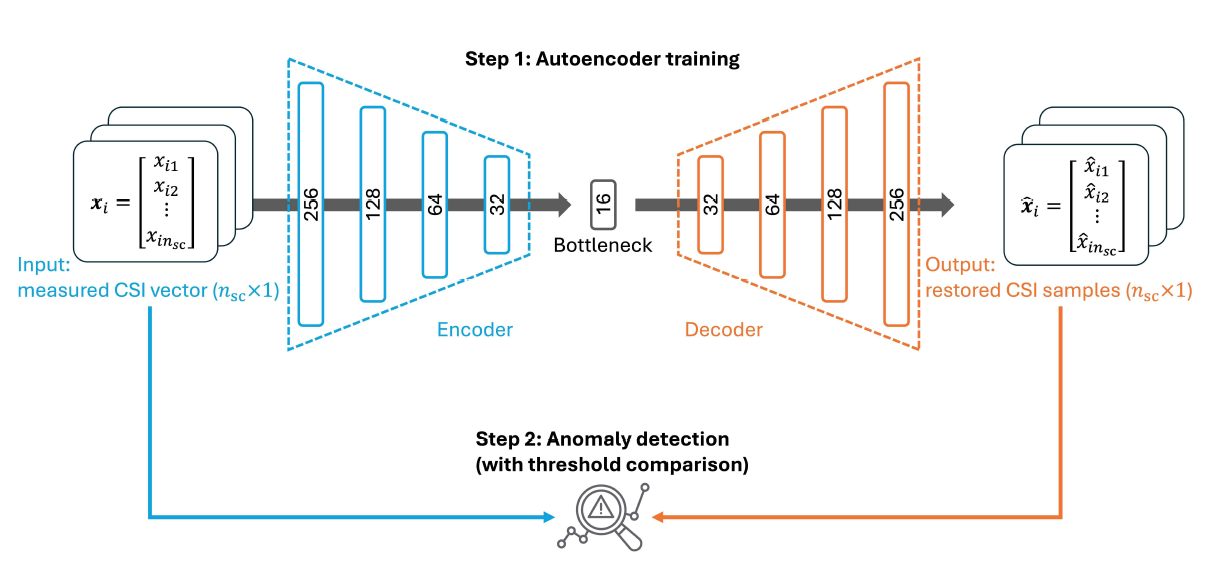

where [TeX:] $$n_{\mathrm{sc}}$$ is the number of subcarriers, which is set to 242 for a 20 MHz bandwidth in the IEEE 802.11ax. Thus, Alice can estimate CSI from any received signals and also ask Bob to repeat transmission for CSI collection. The adversary’s primary objective is to bypass Alice’s authentication, which could serve as an entry point for more sophisticated cyberattacks (e.g., malware injection into a router). It is assumed that conventional authentication protocols can be compromised, making physical layer authentication (PLA) the primary security measure. We also consider that an adversary is placed or moving close to Bob with short distance of d cm to increase the possibility of passing the authentication with similar channel properties to that of Bob. This model assumes a passive and nearby adversary who attempts to mimic the CSI profile of the legitimate user. This is a realistic and challenging case. It is worth noting that more sophisticated attack models, such as replay attacks, signal amplification, coordinated adversarial nodes, or mobile relays, could be deployed in practice. However, these types of active and cooperative adversaries remain outside the scope of this study but are important directions for future investigation, particularly to evaluate the robustness of the proposed framework against higher-layer attacks and physical-layer impersonation strategies. Remark 1. Fig. 2 shows CSI samples from Bob and the adversary in stationary and mobile scenarios (on the top of the next page). In the stationary scenario (Fig. 2a ), a clear distinction is observed, whereas in the mobile scenario (Fig. 2b), the difference is less apparent due to CSI variations. While ML-based PLA schemes work well in stationary environments, they struggle in mobile settings, highlighting the need for more robust deep learning-based anomaly detection models for improved accuracy. Ⅲ. Autoencoder-based PLAThis section presents our proposed autoencoderbased PLA scheme, detailing the autoencoder architecture and the anomaly detection criterion. The proposed scheme leverages only legitimate users’ CSI data to effectively learn the temporal and spatial differences between legitimate users (i.e., Bob) and adversaries in mobile environments. The overall framework is illustrated in Fig. 3 with each step discussed in the following subsections. Unlike classification- based approaches that require labeled examples of both legitimate users and adversaries, the proposed autoencoder is trained solely on legitimate users’ data, allowing it to learn the manifold of authorized CSI patterns. This design mitigates the practical limitation of requiring adversary CSI data and enables anomaly detection based on reconstruction errors, which reflect deviation from the legitimate distribution. Additionally, by capturing nonlinear temporal and spatial relationships in CSI, the autoencoder is more robust to mobility-induced channel variations. 3.1 Autoencoder ArchitectureIn Step 1 of Fig. 3, the proposed autoencoder network processes CSI samples from either a legitimate user or an adversary. The input consists of CSI values across multiple subcarriers, with a dimensionality of [TeX:] $$n_{\mathrm{sc}} \times M,$$ where M represents the number of features considered. In this study, M = 1 as only the absolute amplitude of CSI values is used. Previous studies, such as [11], have shown that magnitude-based features outperform complex CSI for authentication tasks, as magnitude is less influenced by phase variations due to carrier frequency offset, making it more robust in dynamic environments. The autoencoder architecture consists of a symmetric encoder-decoder structure with a bottleneck layer for dimensionality reduction and feature extraction. The encoder reduces CSI data through fully connected layers, with neuron sizes 256 → 128 →64 → 32 → 16, while the decoder reconstructs it symmetrically (16 → 32 → 64 → 128 → 256). The ReLU activation function is applied to all layers except the final output layer, which employs linear activation. The model is trained by minimizing the mean squared error (MSE) using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of [TeX:] $$10^{-4},$$ and early termination is implemented to prevent overfitting. The training process uses a batch size of 64 and is executed over a maximum of 100 epochs, with early stopping triggered if the validation loss does not improve for 10 consecutive epochs. These configurations ensure stable convergence while preserving generalization. 3.2 Anomaly Detection CriterionOnce the autoencoder is trained, it is used for anomaly detection. As described in step 2 of Fig. 3, the proposed autoencoder-based PLA scheme compares the input CSI data [TeX:] $$\mathbf{x}_i=\left[x_{i 1}, \cdots, x_{i n_{\mathrm{sc}}}\right]^T$$ and the reconstructed one [TeX:] $$\hat{\mathbf{x}}_i=\left[\hat{x}_{i 1}, \cdots, \hat{x}_{i n_{\mathrm{sc}}}\right]^T,$$ where i indicates the data index. We define the reconstruction error [TeX:] $$\varepsilon_i$$ for the input CSI data i based on MSE between [TeX:] $$\mathbf{x}_i \text { and } \hat{\mathbf{x}}_i$$ as follows:

(3)[TeX:] $$\varepsilon_i=\frac{1}{n_{\mathrm{sc}}} \sum_{j=1}^{n_{\mathrm{sc}}}\left(x_{i j}-\hat{x}_{i j}\right)^2 .$$Finally, we consider threshold-based comparison for anomaly detection, which is given by

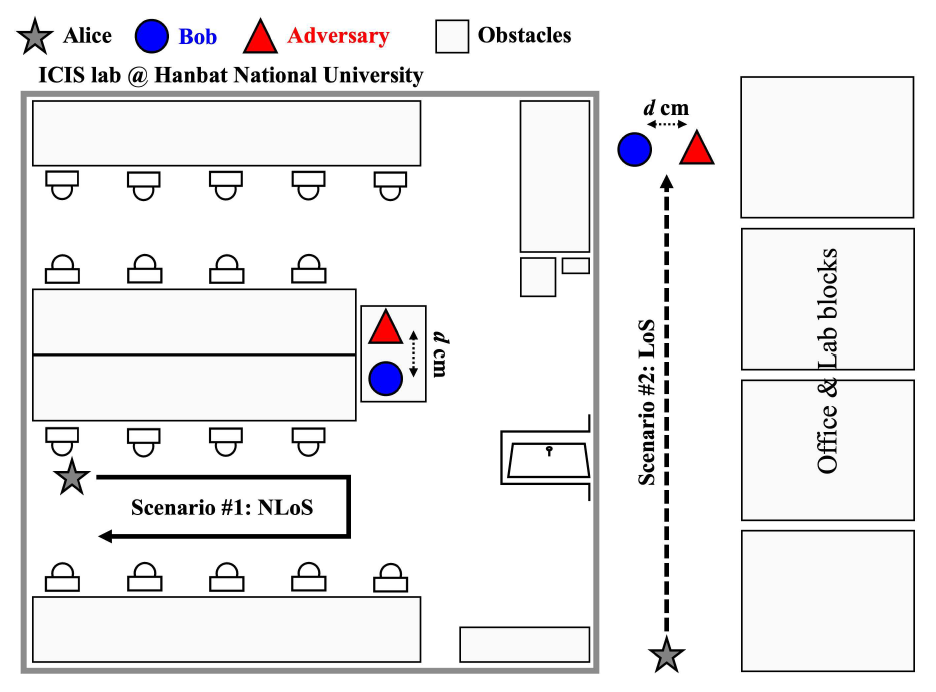

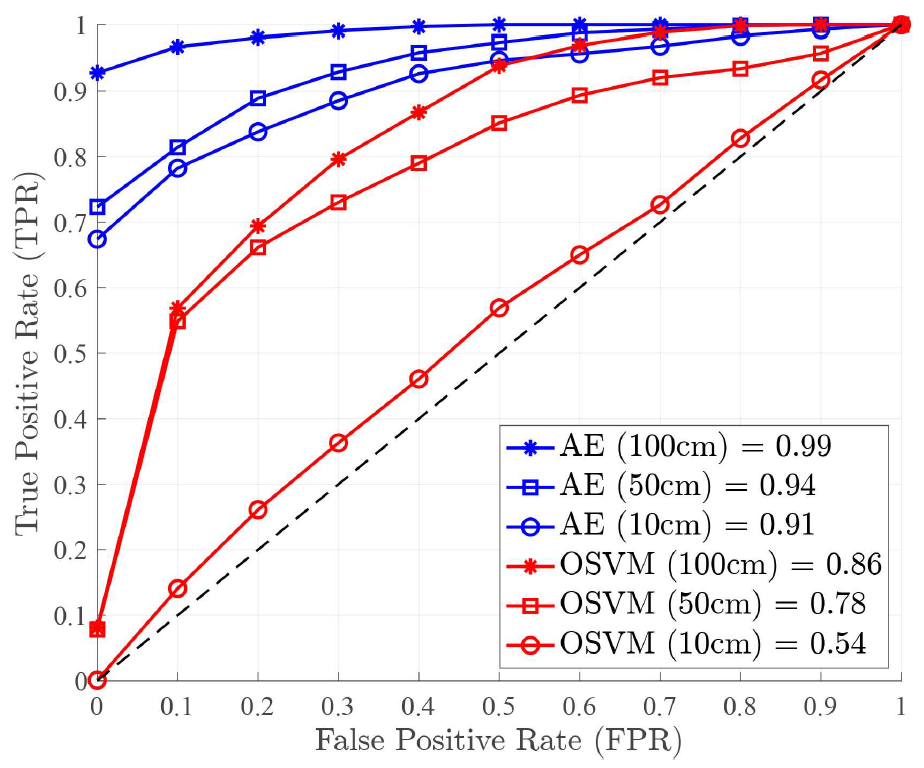

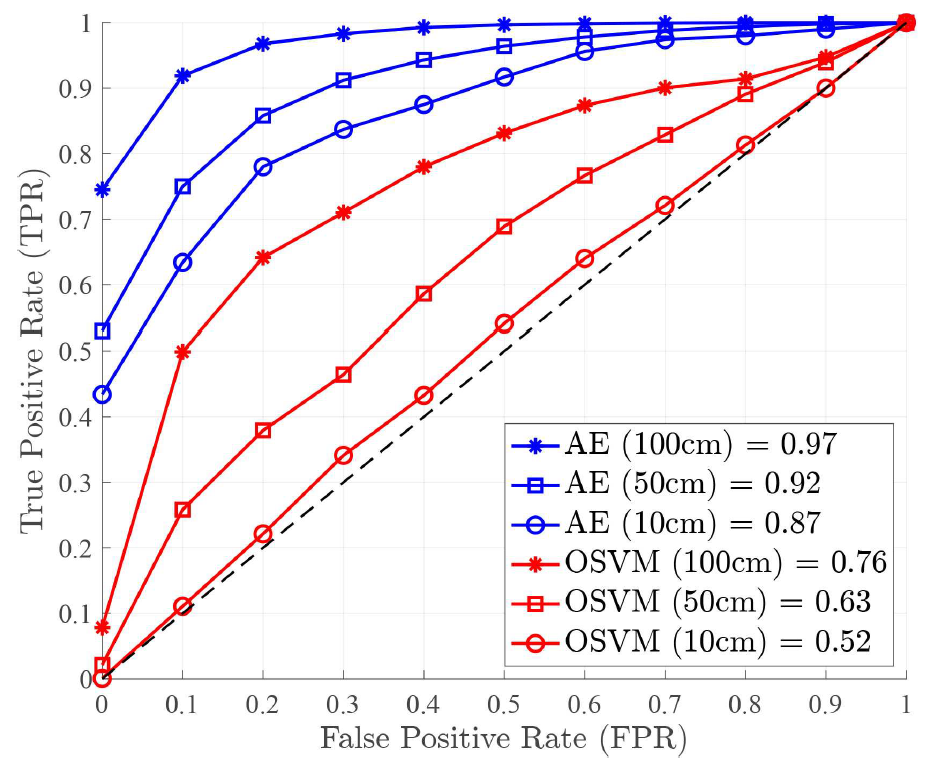

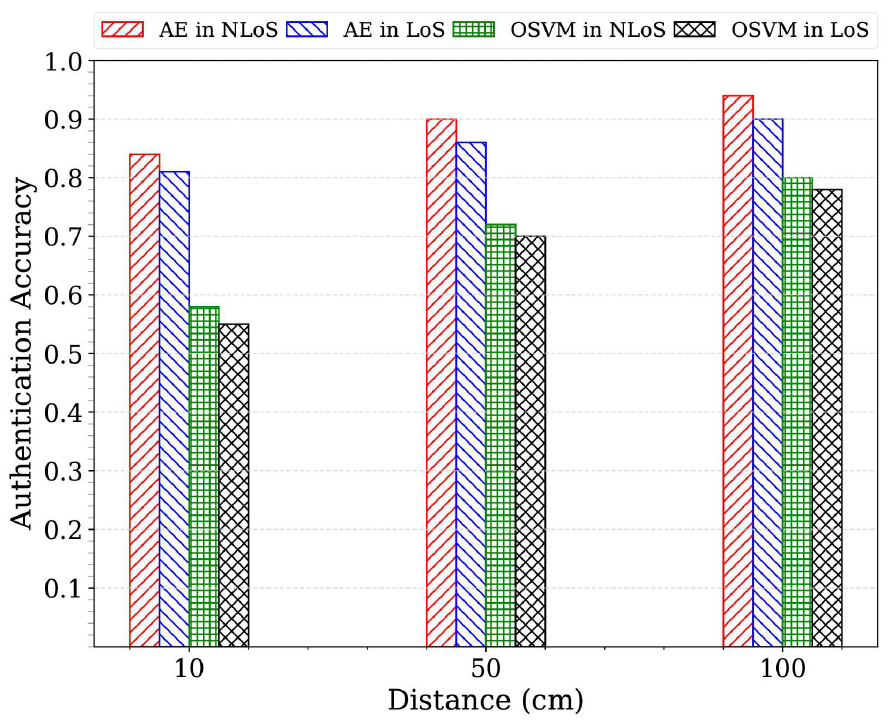

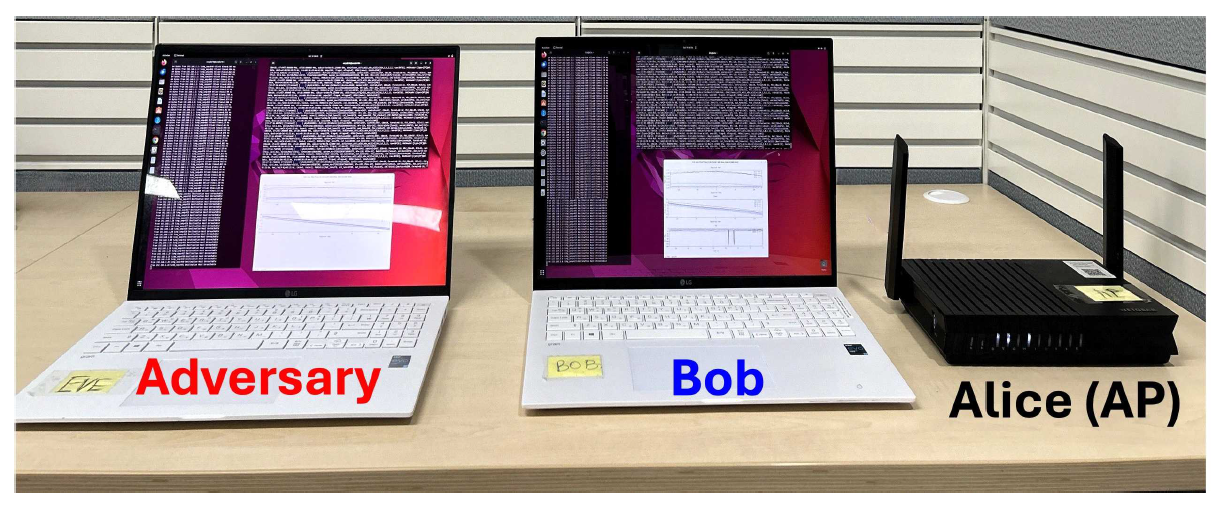

(4)[TeX:] $$r_i= \begin{cases}1, & \text { if } \varepsilon_i \gt T_0, \\ 0, & \text { otherwise, }\end{cases}$$where [TeX:] $$T_0$$ denotes a pre-determined threshold value and [TeX:] $$r_i$$ represents a detection result for input data index i and it indicates anomaly CSI data for [TeX:] $$r_i=1$$ (i.e., CSI data from adversary) and legitimate CSI data for [TeX:] $$r_i=0,$$ respectively. Remark 2. In scenarios where adversarial data is unavailable- such as during real-world deployment-the optimal threshold T0 cannot be computed using metrics that depend on both legitimate and adversarial labels. To address this limitation, we adopt an adaptive thresholding scheme that estimates the decision boundary based solely on the distribution of reconstruction errors from legitimate users during training. Specifically, the optimal threshold is selected based on the 90th quantile of the reconstruction error distribution, ensuring that the majority of legitimate samples fall below this boundary. This approach enables unsupervised deployment and preserves anomaly detection capabilities in the absence of ground-truth adversarial data, making it more suitable for practical implementation in dynamic wireless environments. Ⅳ. Performance EvaluationThis section investigates our experimental setup, scenarios, and results of the proposed PLA scheme compared to the existing OSVM-based approach. 4.1 Experimental SetupThe experiment configures Alice as a Wi-Fi 6 access point (AP), as shown in Fig. 4. The AP is a NETGEAR AX1800 (RAX20) model, supporting the IEEE 802.11ax standard. We operate on a 20 MHz bandwidth within the 2.4 GHz frequency band, utilizing 242 subcarriers for CSI measurement. Bob and the adversary are high-performance laptops with Intel i7 (8-core CPU), 16GB RAM, and Intel AX201 NICs, running Ubuntu 20.04 LTS. This setup represents a controlled indoor environment with homogeneous device capabilities. While this provides reproducible results, future work will extend the evaluation to more diverse scenarios, such as 5 GHz band, outdoor line-of-sight and non-line-of-sight settings, and heterogeneous chipsets. These steps are essential to assess the method’s robustness under more challenging wireless conditions. Fig. 4. Experiment setup: NETGEAR AX1800 (RAX20) model used as AP (Alice) and two laptops equipped with Intel AX201 NIC used for Bob and the adversary  To collect and analyze CSI data, we employ the PicoScenes open-source software[13], which enables fine-grained CSI extraction from commodity Wi-Fi devices, providing a flexible framework for wireless signal analysis research. 4.2 Experimental ScenariosWe conducted our experiment in our laboratory and near places located on the sixth floor of the N4 building at Hanbat National University, South Korea. Fig. 5 shows details of our experimental scenarios. We consider two experimental scenarios considering non lineof-sight (NLoS) and line-of-sight (LoS) environments. For the NLoS scenario, the presence of obstacles and reflections within the laboratory introduces significant variability in the wireless channels. For the LoS scenario, a direct LoS is guaranteed and thus clearer signal propagation is expected, minimizing interference from obstacles and enhancing the reliability of CSI measurements. A total of 50,000 CSI frames were collected across all scenarios at a rate of 100 frames per second. The data was split 70% for training and 30% for testing, with 10% of the training data used for validation. This evaluation assumes only one legitimate user and one adversary with dedicated channel access. However, realistic wireless environments often involve multiple users, devices, and interfering traffic. Future experiments will incorporate crowding effects and concurrent transmissions to investigate the scalability and interference resilience of the proposed scheme. Bob and the adversary remain fixed at a distance d cm apart, while Alice moves to induce channel variations. This setup is equivalent to moving Bob and the adversary while keeping Alice stationary, allowing precise control over spatial separation. CSI samples were collected from both Bob and the adversary, but only Bob’s samples were used to train the proposed autoencoder-based PLA scheme. Both devices continuously ping the AP at 0.01 second intervals. The experiments were conducted at three distances: 10 cm, 50 cm, and 100 cm, to assess how proximity influences the PLA system’ s ability to detect adversarial presence. 4.3 Performance MetricsThe performance of the proposed PLA scheme is evaluated using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the curve (AUC). The ROC curve visually represents the trade-off between the true positive rate and the false positive rate across various decision thresholds, providing insight into the model’s ability to distinguish between legitimate and adversarial users. The AUC quantifies the overall performance of the model by measuring the area beneath the ROC curve, where a higher AUC value signifies greater classification accuracy and improved adversary detection capabilities. 4.4 Experimental ResultsThe OSVM model-based PLA scheme (shortly, OSVM in this subsection) as the baseline scheme during the performance evaluation of our autoencoderbased PLA scheme (shortly, AE in this subsection). Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 present the performance comparison between AE and OSVM across different distances in both NLoS and LoS scenarios. The AUC results confirm that AE consistently outperforms OSVM at all tested distances in both environments. Moreover, the findings indicate that increasing the distance d between Bob and the adversary enhances authentication accuracy. This improvement arises due to reduced spatial correlation in CSI, making it increasingly difficult for the adversary to replicate Bob’s CSI characteristics. The AE model effectively leverages these differences, achieving superior anomaly detection and authentication accuracy. Although the current work compares only with OSVM as a baseline, which also adheres to a one-class learning framework, future research will incorporate additional deep learning models such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and transformer- based architectures. These comparisons will help determine whether the unsupervised autoencoder remains superior when attacker labels are unavailable, or if supervised models can perform better under relaxed assumptions. Fig. 8 illustrates that both AE and OSVM models achieve higher authentication accuracy in NLoS scenarios compared to LoS environments. Specifically, the AE model attains authentication accuracies of 0.84, 0.90, and 0.94 at distances of 10 cm, 50 cm, and 100 cm in NLoS, whereas in LoS, the accuracy slightly decreases to 0.81, 0.86, and 0.90, respectively. A similar pattern is observed for OSVM, where accuracy is lower in LoS than in NLoS. In particular, OSVM achieves 0.58, 0.72, and 0.80 in NLoS, whereas in LoS, it records 0.55, 0.70, and 0.78 at distances of 10 cm, 50 cm, and 100 cm, respectively. The observed performance gap between NLoS and LoS environments is attributed to the increased multipath effects in NLoS, which introduces more pronounced variations in CSI. These variations make it significantly more challenging for an adversary to imitate Bob’ s CSI patterns, thereby strengthening the security of the proposed scheme. In Table 1, we assess the impact of threshold selection sensitivity, we consider three cases: a lower threshold [TeX:] $$R_L$$ (corresponding to the 80th percentile), the adopted threshold [TeX:] $$T_0$$ at the 90th percentile, and a higher threshold [TeX:] $$T_H$$ (corresponding to the 95th percentile) of the reconstruction error distribution. The authentication performance of the proposed AE model is evaluated across these thresholds. In the LoS scenario, all three threshold configurations yield relatively high accuracy, particularly at longer distances. However, in the NLoS scenario, only the 90th percentile threshold consistently achieves high authentication accuracy across all evaluated distances, whereas both the lower and higher percentile thresholds result in performance fluctuations due to the increased channel variability introduced by multipath effects. These results confirm the robustness and reliability of the adaptive thresholding strategy, demonstrating its suitability for unsupervised deployment in dynamic and complex wireless environments. Ⅴ. ConclusionIn this paper, we investigated the autoencoder- based physical layer authentication framework that only exploits legitimate users’ channel state information (CSI) data to efficiently learn the temporal and spatial differences between legitimate users and adversaries in the mobile scenario. We performed extensive experiments by collecting many CSI data samples for training and evaluation in both non line-of-sight and line-of-sight scenarios. Our experimental results verified that the proposed autoencoder- based PLA scheme outperforms the existing one in terms of authentication accuracy in dynamic wireless environments. Future research aims to study additional physical layer features to enhance authentication accuracy and resilience against adversaries. BiographyRalph Kumah Assan2021 : B.Eng., Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Ghana 2025 : M.Eng., Hanbat National University, South Korea 2025~Current : Ph.D. Candidate Student, Departmnet of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Portland State University, USA [Research Interest] Wireless network security, physical layer security, physical layer authenti- cation. [ORCID:0009-0007-3247-7443] BiographyJihwan Moon2019 : Ph.D. Electrical Engin- eering, Korea University, South Korea 2019~2019 : Post-Doctoral Re- search Associate, Korea University, South Korea 2019~2020 : Senior Researcher, Affiliated Institute of ETRI, South Korea 2020~2022 : Assistant Professor, Department of Information and Communication Technology, Chosun University, South Korea 2022~Current : Assistant Professor, Department of Mobile Convergence Engineering, Hanbat National University, South Korea [Research Interest] Optimization techniques, energy harvesting, physical-layer security, wireless surveillance, covert communications, and machine learning for wireless communications. [ORCID:0000-0002-9812-7768] BiographyTaehoon Kim2017 : Ph.D. Electrical Engin- eering, KAIST, South Korea 2017~2020 : Senior Researcher, Agency for Defense Develo- pment, South Korea 2020~Current : Associate Profe- ssor/Assistant Professor, De- partment of Computer Engineering, Hanbat National University, South Korea [Research Interest] Wireless communications, satellite communications, machine learning for wireless communications, and wireless network security. [ORCID:0000-0002-9353-118X] BiographyInkyu Bang2017 : Ph.D. Electrical Engin- eering, KAIST, South Korea 2017~2019 : Research Fellow, National University of Singapore, Singapore 2019~2019 : Senior Researcher, Agency for Defense Develo- pment, South Korea 22019~Current : Associate Professor/Assistant Profe- ssor, Department of Intelligence Media Engin- eering, Hanbat National University, South Korea [Research Interest] Information-theoretic security (physical-layer security), mobile network security in 5G/6G, satellite communication, and AI applications in wireless communication systems. [ORCID::0000-0001-7109-1999] References

|

StatisticsCite this articleIEEE StyleR. K. Assan, J. Moon, T. Kim, I. Bang, "Physical Layer Authentication for Mobile Devices in WLAN Systems: An Autoencoder-Based Approach," The Journal of Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences, vol. 50, no. 11, pp. 1660-1668, 2025. DOI: 10.7840/kics.2025.50.11.1660.

ACM Style Ralph Kumah Assan, Jihwan Moon, Taehoon Kim, and Inkyu Bang. 2025. Physical Layer Authentication for Mobile Devices in WLAN Systems: An Autoencoder-Based Approach. The Journal of Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences, 50, 11, (2025), 1660-1668. DOI: 10.7840/kics.2025.50.11.1660.

KICS Style Ralph Kumah Assan, Jihwan Moon, Taehoon Kim, Inkyu Bang, "Physical Layer Authentication for Mobile Devices in WLAN Systems: An Autoencoder-Based Approach," The Journal of Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences, vol. 50, no. 11, pp. 1660-1668, 11. 2025. (https://doi.org/10.7840/kics.2025.50.11.1660)

|