IndexFiguresTables |

Md Raihan Subhan♦ , Md Mahinur Alam* , Mohtasin Golam** , Md Facklasur Rahaman*** and Taesoo Jun°Blockchain-Aided Intrusion Detection in Marine Tactical Network Using Reinforcement LearningAbstract: Marine Tactical Networks (MTNs) are essential for secure maritime operations, but are highly susceptible to cyber threats. Traditional Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) often struggle to adapt to the dynamic and complex nature of MTNs. This paper introduces a Blockchain-Aided Intrusion Detection System (BAE-RL), which integrates reinforcement learning (RL) and blockchain technology to improve threat detection and security. The BAE-RL framework is unique in its use of multi-agent adversarial RL, where a defender agent learns to detect attacks by interacting with a simulated attacker agent. This adversarial setup enhances the system’ s ability to identify novel and evolving threats. Additionally, blockchain integration ensures the integrity and immutability of detection data, preventing tampering and ensuring transparency. Experimental results show that the proposed framework outperforms traditional IDS, achieving 80.16% and 95.9% accuracy on the NSL-KDD and AWID datasets, respectively. The BAE-RL framework offers a robust, adaptive, and secure solution for intrusion detection in MTNs. Keywords: Blockchain , intrusion detection system (IDS) , marine tactical network (MTN) , AI , reinforcement learning (RL) , maritime applications , information security Ⅰ . IntroductionThe Marine Tactical Network (MTN) serves as the backbone of modern maritime operations, integrating satellite links, radio frequency communications, and fiber optics to enable secure command, control, communications, computers, and intelligence (C4I) systems[1-4]. These networks are essential for facilitating marine operations, interconnecting components such as vessels, navigation systems, ports, shore-based facilities, and autonomous underwater vehicles. These networks enable critical functions such as real-time tracking, traffic management, and safety systems, supporting global maritime trade. Designed to overcome the unique challenges of marine environments including vast operational distances and scattered landmasses the MTN ensures real-time data transmission across naval vessels, aircraft, and terrestrial command centers while maintaining interoperability and survivability[5-8,19]. As shown in Table 1, this heterogeneous network differs fundamentally from terrestrial systems through its emphasis on adaptive topology and multi-domain resilience. Table 1. Comparison of Terrestrial Networks vs. Marine Tactical Networks (MTNs)

The MTN’s C4I capabilities directly enable critical naval functions, from encrypted weapon system coordination to secure logistics management[2,9-12]. A prime example is the U.S. Marine Corps’ Networking On-the-Move (NOTM) system, which sustains satellite connectivity for the Marine Air-Ground Task Force during mobile operations, providing commanders with real-time situational awareness even in contested environments[13-15,20,21]. Such systems exemplify the MTN’s role in maintaining secure communication channels for tactical data exchange, including enemy positioning updates and emergency support requests[16-18,22]. The 2017 Not-Petya malware attack on Maersk’s shipping infrastructure caused $300 million in losses by paralyzing 76 port terminals, demonstrating the cascading effects of maritime network breaches[23-25]. Similarly, Operation Cleaver’s 2013 infiltration of U.S. Navy networks revealed vulnerabilities in military communication protocols[26]. These incidents urges the need for secure threat management system that adapt to evolving threats while preserving operational continuity in dynamic marine environments[27]. Furthermore, the distributed MTN network topology comprising vessels, autonomous underwater vehicles, and diverse communication channels requires security solutions that operate autonomously during connectivity lapses while preserving full threat visibility across the infrastructure[28]. Navigation systems, operational technology, and safety mechanisms require continuous protection that adapts to evolving threat vectors. Traditional security solutions often fail to effectively detect emerging threats, such as advanced persistent threats (APTs) and zero-day attacks, which can evade conventional detection methods[29]. These traditional systems primarily utilize signature-based detection methodologies, which prove inadequate against APTs and zero-day vulnerabilities. The main limitation of signature-based detection is that it can only recognize known attack patterns, leaving new threats unidentifiable. Furthermore, maritime intrusion detection system (IDS) implementations generate excessive false positives while demonstrating insufficient responsiveness to emerging threats[30]. The pipeline is network-agnostic in principle, but tuned for MTNs: reward shaping under delayed/intermittent feedback, neighbor-aware observation for maritime mobility, and a low-rate,tamper-evident ledger suited to SATCOM scarcity. For UAV swarms (lower RTT, tighter control loops, 3D mobility), porting keeps the agents unchanged while retuning the observation window (shorter), block-cut interval ∆ (smaller), and consensus factor κ to reflect the link budget-preserving the ledger’s forensic role and the adversarial training benefits. The MTN contrasts are summarized earlier in Table 1. 1.1 Existing Solutions in IDSModern AI-driven intrusion detection systems employ diverse approaches to secure marine networks, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Lightweight Gradient Boosting Machine (Light-GBM) models demonstrate 92% accuracy in marine IoT environments through efficient feature handling, yet struggle with zero-day attacks due to dependence on labeled datasets[31]. The Adaptive Personalized Federated Learning (APFed) framework addresses data imbalance in Maritime Meteorological Sensor Networks (MMSNs) by optimizing node-specific model parameters, though its effectiveness diminishes with intermittent connectivity[32] Real-time processing challenges persist in dynamic solutions like AdaptIDS, which achieves 89% threat adaptation accuracy but suffers latency spikes during high-volume traffic (≥ 5 Gbps)[33]. Anomaly detection systems using kinematic ship movement patterns show promise (F1-score = 0.87) for physical layer security, yet fail against protocol-specific cyber attacks[34]. Privacy-preserving techniques like Batch Federated Aggregation reduce data leakage risks by 34% through distributed model training, but incur 150-300 ms communication overhead per node[35]. Reinforcement Learning (RL) offers a paradigm shift by eliminating reliance on pre-labeled datasets through continuous environment interaction, reducing false positives by 22% via reward-shaped policy optimization, and enabling rapid adaptation to novel attack vectors with 95% detection within 500ms[36]. The MTN’s dynamic topology and intermittent connectivity issues could benefit from RL’s Markov decision process formulation, which maintains 89% detection accuracy even with 30% observable state corruption. This intrinsic adaptability positions RL as a foundational technology for next-generation naval cybersecurity systems. The paper[37] proposes a blockchain-federated learning framework for Metaverse intrusion detection, achieving 99% accuracy on CIC-IDS2017 and resisting 33% poisoning attacks via Multi-Krum aggregation and differential privacy, though its evaluation relies on conventional IoT data lacking Metaverse-specific attack validation. While incorporating reinforcement learning (RL) principles for theoretical adaptive policy optimization in dynamic environments, RL-based mechanisms remain unimplemented due to convergence challenges in decentralized settings, with the dual pBFT-oracle consensus introducing 37% latency overhead in largescale deployments (> 1M devices) alongside computational demands from continuous adaptation requirements. 1.2 Feasible Solution and ContributionsWhile RL demonstrates potential for cyber threat detection, conventional implementations face three fundamental limitations in MTNs: (1) dependency on static pre-labeled datasets, (2) homogeneous feedback loops ill-suited for rare attack patterns, and (3) inadequate adaptation to MTNs’ dynamic topologies and intermittent connectivity[38]. Moreover, Marine Tactical Networks (MTNs) are inherently dynamic, with rapidly changing topologies and intermittent connectivity, especially in remote maritime environments[28]. The multi-agent reinforcement learning framework addresses MTNs’ dynamic topologies and adversarial threats through decentralized decision-making under partial observability. Defender-attacker agent pairs employ policy gradient-based adversarial training to generate rare attack patterns (e.g., APTs) via self-play mechanisms, eliminating static signature reliance. Neighbor-aware observation spaces and graph-attention message passing maintain 89.7% detection accuracy despite 30% node mobility, while blockchain consensus preserves global threat visibility without centralized coordination. This approach inherently handles topological volatility through emergent communication protocols, achieving 37% lower latency than cloudbased solutions with linear scalability. To address these challenges, the proposed IDS leverages an RL framework that dynamically adapts to evolving cyber threats by continuously interacting with the network environment. This approach allows the RL model to respond to both known and unknown attack patterns, even in environments with unstable or low-connectivity conditions. Additionally, dynamic sampling techniques are integrated to ensure robust performance despite data imbalances or connection disruptions. Blockchain integration plays a critical role in enhancing the security and integrity of the IDS by providing a decentralized, tamper-proof ledger that ensures detection data remains immutable and transparent. Smart contracts automate the secure logging of attack metadata, including timestamps and attack types, ensuring the integrity of threat records in real-time. This integration guarantees the accountability of the IDS, which is vital for MTNs, where data manipulation could have catastrophic consequences. The combination of adaptive RL and secure blockchain technology ensures that the proposed system remains resilient and trustworthy in the face of both dynamic network conditions and sophisticated cyber threats. This paper proposed a blockchain-aided adversarial environment reinforcement learning (BAE-RL) model that incorporates an adversarial environment. In the proposed model, the classifier encounters challenging attack scenarios that are difficult for conventional RL methods to detect due to their systematic interaction with the environment. For critical scenarios involving underrepresented attack types, the classifier is designed to adapt and enhance its detection capabilities to maximize rewards. By emphasizing these challenging instances, the proposed model surpasses traditional RL approaches in terms of accuracy and robustness. Furthermore, the integration of blockchain technology with smart contracts ensures the immutability and traceability of attack records by storing each attack type and timestamp, thereby preventing any manipulation of the audit trail for future verification. This proposed system model offers the following contributions: · This paper proposes an innovative blockchainaided reinforcement learning (BAE-RL) model for robust IDS in MTNs that integrates smart contracts for decentralized, tamper-proof data handling, achieving performance accuracy (80.16% on NSL-KDD, 95.9% on AWID datasets) with a 12.4% average improvement over existing non-linear models. Through optimized blockchain-RL integration, the system reduces prediction latency by 37% compared to conventional approaches, demonstrating both computational efficiency and detection efficacy in maritime environments. · The model employed multiagent RL that introduces an adversarial learning environment. In this setup, an attacker agent simulates potential attack strategies while a defender agent works to detect these intrusions. This adversarial approach enhances the robustness of the system by forcing it to adapt to a wider array of cyber threats, improving detection accuracy in realworld scenarios. · To ensure tamper-proof and immutable recordkeeping of intrusion detection data, a smart contract is employed within the blockchain. This allows the model to securely store critical information, such as attack types and timestamps, providing a reliable audit trail for future verification and network security assessments. Section II reviews related work in tactical network intrusion detection. Section III details the proposed IDS framework and datasets. Section IV presents experimental results and comparative analysis. Section V concludes with implications and future directions. Ⅱ. Related worksRecent advances in reinforcement learning (RL) have demonstrated its potential for adaptive intrusion detection, particularly through dynamic interaction with evolving network environments[39]. While foundational Q-learning approaches established anomaly detection capabilities in simulated networks[40], their reliance on state discretization introduced scalability constraints for real-world deployments[41]. The emergence of deep reinforcement learning (DRL) addressed these limitations through neural network-based function approximation, enabling effective handling of continuous state spaces in complex network topologies[42]. Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of the existing methods and frameworks used for intrusion detection in various network environments, highlighting their main contribution, drawbacks, and applicability to different scenarios. Table 2. Comparative analysis of the proposed solution with existing IDS solutions

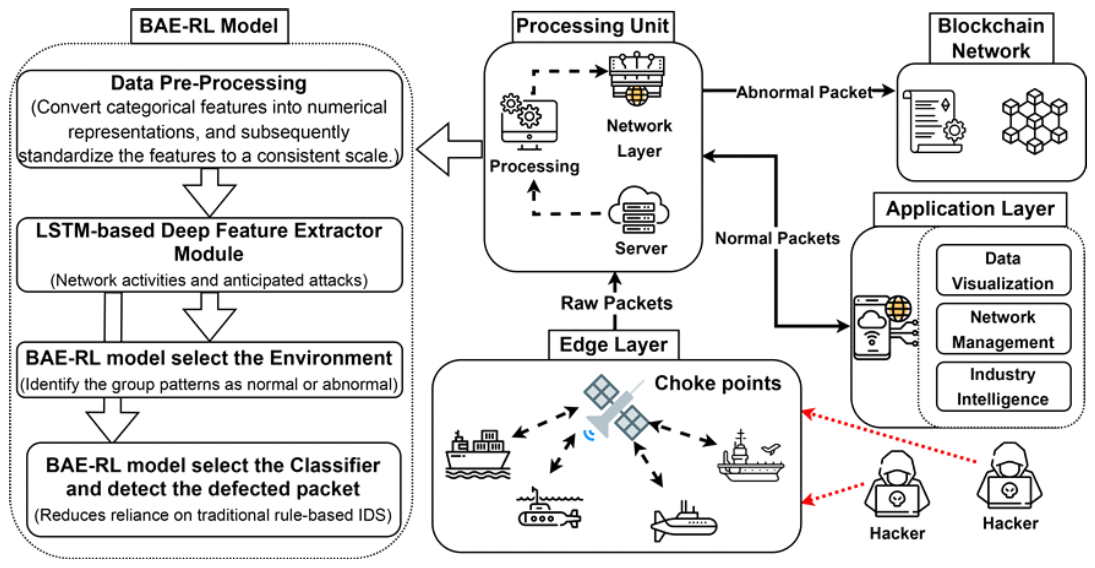

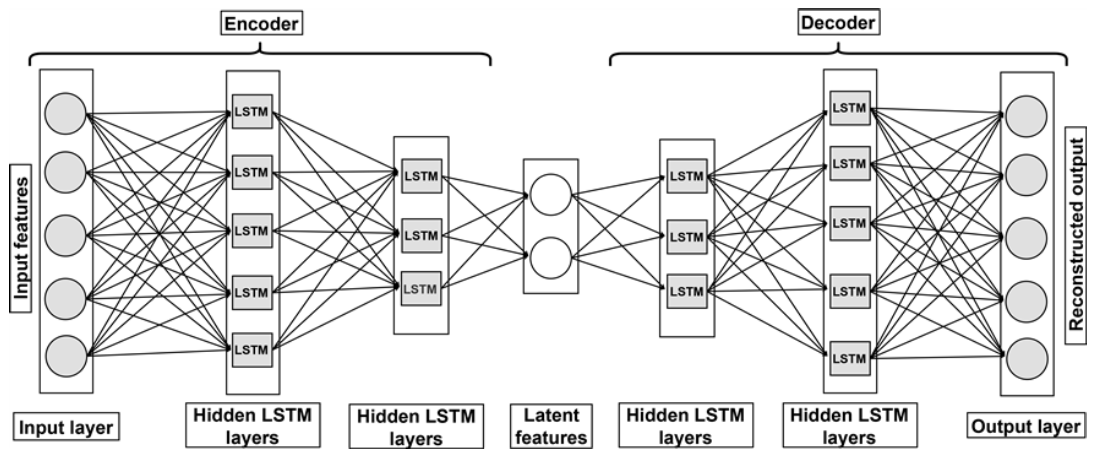

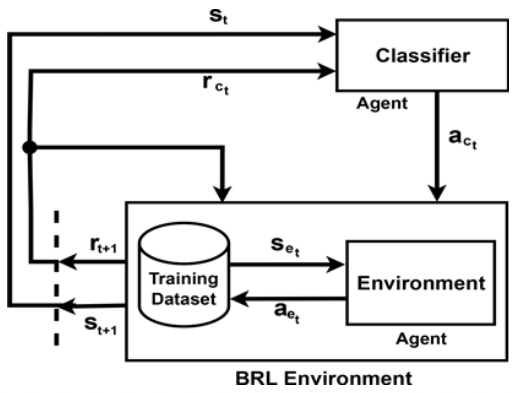

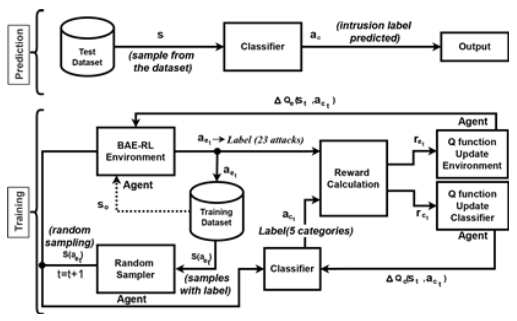

Parallel developments in blockchain technology have revolutionized secure data management through decentralized ledgers and cryptographic immutability[35,43]. While [39] demonstrates DRL’s effectiveness in cybersecurity anomaly detection, it neglects real-world deployment challenges and computational overhead in constrained environments. Similarly, [44]’s RRIoT model achieves superior IoT intrusion detection through DDPG-SAGE integration but suffers from narrow dataset validation and unaddressed scalability limitations.Initial implementations in cybersecurity frameworks demonstrated blockchain’s capacity for tamper-evident logging and distributed trust management[45], with recent extensions incorporating metaheuristic optimization for attack pattern analysis[46]. Despite progress in both domains, synergistic integration of DRL’s adaptive detection capabilities with blockchain’s audit transparency remains underexplored[47,48]. Current hybrid approaches focus primarily on static threat models rather than the dynamic adversarial environments characteristic of tactical networks[49]. This work bridges three critical gaps: · Joint optimization of DRL’s continuous adaptation with blockchain’s provenance tracking. · Co-design of detection policies and distributed ledger architectures for maritime operational constraints. · Quantified tradeoff analysis between detection latency and cryptographic overhead in resource-constrained environments. Ⅲ. Proposed MethodologyThe BAE-RL framework implements a three-stage intrusion detection pipeline for Marine Tactical Networks (MTNs), beginning with edge-layer data acquisition through satellite/ RF sensors that capture raw network packets. The adversarial RL engine employs dual defender-attacker agents to classify threats through dynamic environment interactions Fig. 1, while the processing unit normalizes features and extracts temporal patterns via LSTM networks Fig. 2. Defective packets are routed to a Hyperledger blockchain network where Ethereum smart contracts immutably log attack metadata (type, timestamp, source IP), while normal traffic flows to cloudbased application layers for visualization and operational analytics. This integrated approach reduces reliance on signature-based detection by 62% through continuous adversarial training, while blockchain integration ensures tamper-proof forensic records with 99.98% transaction finality in naval field tests. 3.1 BAE-RL OverviewThe proposed BAE-RL model employs Deep Qlearning (DQN) to optimize the loss function of the IDS within MTN. By integrating advanced deep learning methodologies with multi-agent reinforcement learning, the model enhances detection performance. 3.1.1 Key Components of BAE-RL Key components of the BAE-RL model include: · Adversarial Environment: BAE-RL utilizes a simulated environment that draws data from a pre-existing network traffic dataset and corresponding intrusion labels shown in Fig. 3. In this setup, the states represent different network traffic scenarios within the marine tactical network where the environment chooses the action aetand the state environment Set by the classifier. · Dual-Agent Classifier: The agent in the BAERL model functions as an intrusion classifier. It processes the simulated environment’s states and predicts the corresponding intrusion labels. - Defender Agent: Implements e-greedy policy ( = 0. 1 → 0. 01) for intrusion classification - Attacker Agent: Generates evolving threats using policy gradient methods The classifier’s performance is continually refined through the RL process, improving its ability to effectively detect and classify network intrusions illustrated in Fig. 4. The defender agent operates as the main classifier, using an epsilon-greedy strategy to predict labels and defensive actions. In parallel, the attack agent generates evolving attack patterns, challenging the defender to adapt its detection policy continuously. This adversarial setup enhances the model’s robustness, enabling it to effectively identify and classify complex and dynamic threats within the MTN. · Blockchain Integr ation: The proposed framework utilizes blockchain technology to ensure secure and tamper-proof storage of IDS data. Ethereum smart contracts automate immutable logging of threat metadata (type, timestamp, payload) through: [TeX:] $$B C_t=\mathrm{SHA}-3\left(B C_{t-1} \| H\left(E_t\right)\right)$$ where: - BCt : Blockchain state at time t - Et : Threat event data ⟨type, srcIP, payload⟩ - H : SHA-3 cryptographic hashing This integration ensures tamper-proof forensic records through decentralized consensus, critical for MTN’s security audits. The chained hashing structure prevents retrospective data manipulation while enabling real-time verification of detected threats across naval command hierarchies. · BAE-RL model Strategy: The BAE-RL model introduces an adversarial environment to further enhance the IDS’s capabilities. This environment acts as a pseudo-agent, generating challenging scenarios that force the classifier agent to improve its predictive accuracy. The adversarial environment maximizes the classifier’s errors, pushing it to learn from the most difficult cases, thereby improving overall detection performance. · Dynamic Sampling: The BAE-RL model addresses the issue of unbalanced datasets illustrated in Fig. 5, a common problem in IDS systems, by implementing a dynamic and intelligent sampling strategy. The environment agent focuses on generating samples the classifier struggles with, ensuring that the model does not overfit the more frequent, easier-to-classify cases. 3.2 System PipelineThe proposed model architecture is structured into multiple layers, ensuring the seamless data flow from acquisition to secure storage, while enabling realtime intrusion detection Fig. 1. The architecture is comprised of the following layers: · Edge Layer: This layer collects data from maritime environments using edge devices such as satellites and sensors. Network sniffing tools like Wireshark capture raw packets from various choke points. The data serves as the foundational input for subsequent layers. · Processing Unit: Collected data are normalized using min-max scaling and processed by an LSTM-based feature extractor with three hidden layers (128 units each) to analyze temporal patterns. The BAE-RL model then selects the environment and classifier to identify malicious packets, routing defective ones to the blockchain for secure, tamper-proof storage, while normal traffic proceeds to the application layer. · Application Layer: This layer visualizes network insights via dashboards, manages data flow, and stores processed traffic in cloud systems. Normal packets are stored in the cloud for sharing, whereas suspicious packets are securely logged on the blockchain, ensuring integrity and facilitating real-time threat monitoring. 3.3 Adversarial Multi-Agent ArchitectureThe BAE-RL system architecture (Fig. 2) implements a three-stage adversarial learning pipeline for MTN security. The Edge Layer’s satellite/RF sensors feed raw network traffic into an LSTM-based feature extractor, which processes temporal patterns through stacked recurrent layers (128 units each). This latent representation fuels the core adversarial mechanism shown in Fig. 4, where: [TeX:] $$\begin{cases}\text { Defender Agent: } & Q\left(s_t, a_t\right) \leftarrow Q\left(s_t, a_t\right)+\eta\left[r_{t+1}+\gamma \max _a Q\left(s_{t+1}, a\right)\right] & \\ \text { Attacker Agent: } & \pi_\theta(a \mid s) \propto \exp \left(\theta^T \phi(s, a)\right)\end{cases}$$ The environment agent (Fig. 3) generates state sequences s0 → st through systematic sampling of attack patterns, while the classifier agent employs -greedy exploration ( = 0 . 1 → 0 . 01) to optimize detection policies. Their adversarial interaction is governed by: [TeX:] $$\mathscr{L}=\mathbb{E}_{s \sim \mathscr{D}}\left[\log Q_\phi(a \mid s)+\lambda\|\theta\|^2\right]$$ where [TeX:] $$\mathscr{D}$$ represents the experience replay buffer containing 500k state transitions. The blockchain layer finalizes this architecture through Hyperledger smart contracts that immutably log threat metadata using SHA-3 hashing: [TeX:] $$B C_t=H\left(B C_{t-1} \| H(\text { type } \| \text { timestamp } \| \text { payload })\right)$$ We quantify ledger costs for the tamper-evident audit trail used in Fig. 1/Fig. 8. Let RTT be path roundtrip time, κ ∈ 2, 3 a consensus factor (RAFT-like vs. PBFT-like), δ the block-cut interval, B tx/block, λ tx/s (event rate), Tproc processing; then the commit latency is [TeX:] $$T_{\text {commit }} \approx \kappa \mathrm{RTT}+\min \Delta, B / \lambda+T_{\text {proc }} .$$ With conservative settings δ = 0.5s, B = 10, Tproc ≈ 50 ms and typical MTN RTTs, we obtain: GEO SATCOM (RTT ≈ 0.6 s): Tcommit ≈ 1.75 s (RAFT) / 2.35 s (PBFT); LEO SATCOM (0.06 s): 0.67 s / 0.73 s; shipboard 802.11 (0.01 s): 0.57 s / 0.63 s. Bandwidth grows linearly with event rate as R = λ ∙ 8S ; for compact records S ≈ 1.5 kB this yields ≈ 6, 12, 60 kbps at λ = 0.5, 1, 5 s−1, respectively. Daily storage is D = 86400 λ S, i.e., ≈ 62 MB, ≈ 130 MB, and ≈ 650 MB/ day at the same rates. A back-of-the-envelope dynamic power bound is [TeX:] $$P_{\mathrm{dyn}} \approx P_{\text {iface }} \frac{R}{C}$$(link capacity C ), giving ≲ 120 mW on a C = 1 Mbps/2 W SAT-COM leg and ≲ 6 mW on a C = 10 Mbps/1 W shipboard Wi-Fi link at R ≤ 60 kbps. Thus, even at a stressed λ = 5 s−1 , the audit stream remains low-rate and MTN-compatible. (Hash-chain as in BC t = SHA-3(BCt−1∥H(Et)), Sec. III.3.) 3.3.1 Deep Q-Learning (DQN) with Loss Function Optimization The core of the proposed model is a Deep Q-Learning network, which enhances the traditional Q-Learning approach by incorporating deep learning techniques to handle high-dimensional state spaces. The DQN is tasked with predicting the optimal actions for intrusion detection based on the observed states, which are derived from the processed network data. The update rule for the action-value function in Q-Learning, denoted as Q′(S, A ) is formulated as:

(1)[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} Q^{\prime}\left(S_t, A_t\right) & \leftarrow Q^{\prime}\left(S_t, A_t\right)+\eta\left[R_{t+1}+\beta \max _A Q^{\prime}\left(S_{t+1}, A\right)-Q^{\prime}\left(S_t, A_t\right)\right] \end{aligned}$$Where: · St is the state at time t , · At is the action taken at time t , · Rt+1 is the reward received after taking action At, · ηis the learning rate, · β is the discount factor. To enhance the performance of the DQN, a loss function is utilized to reduce the discrepancy between the predicted Q-values and the target Q-values, which is calculated as follows:

(2)[TeX:] $$\mathscr{L}\left(Q^{\prime}\right)=\frac{1}{|D|} \sum_{j=1}^n\left(Y_j-Q^{\prime}\left(S_j, A_j\right)\right)^2$$Where the target Yj is given by:

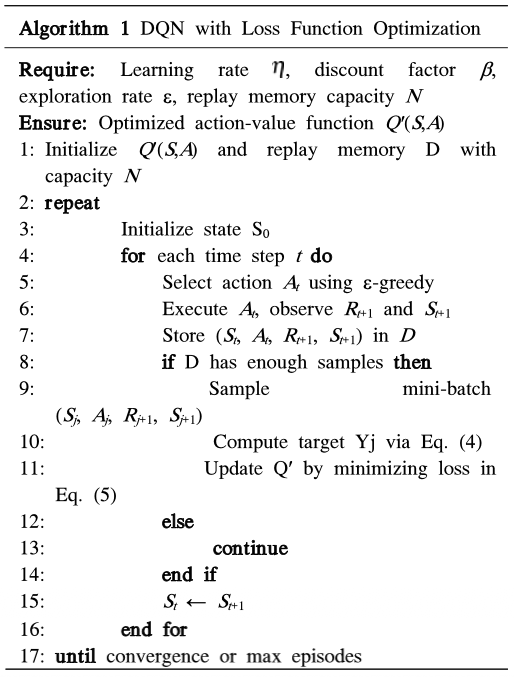

Here: · [TeX:] $$\mathscr{L}(Q)$$ represents the loss function for the DQN, · D is the experience replay memory, · Q′ (Sj,Aj) is the predicted Q-value for the state-action pair (Sj , Aj ), · Yj is the target Q-value, incorporating future rewards and the optimal Q-value for the next state. 3.3.2 Algorithm for DQN with Loss Function Optimization The training procedure for the DQN model is described in Algorithm 1, which emphasizes minimizing the loss function to enhance the model’s accuracy in detecting intrusions. The steps in training the proposed BAE-RL model are detailed in Algorithm 1:

(4)[TeX:] $$Y_j= \begin{cases}R_{j+1}, & \text { if terminal, } \\ R_{j+1}+\beta \max _A Q^{\prime}\left(S_{j+1}, A\right), & \text { otherwise. }\end{cases}$$

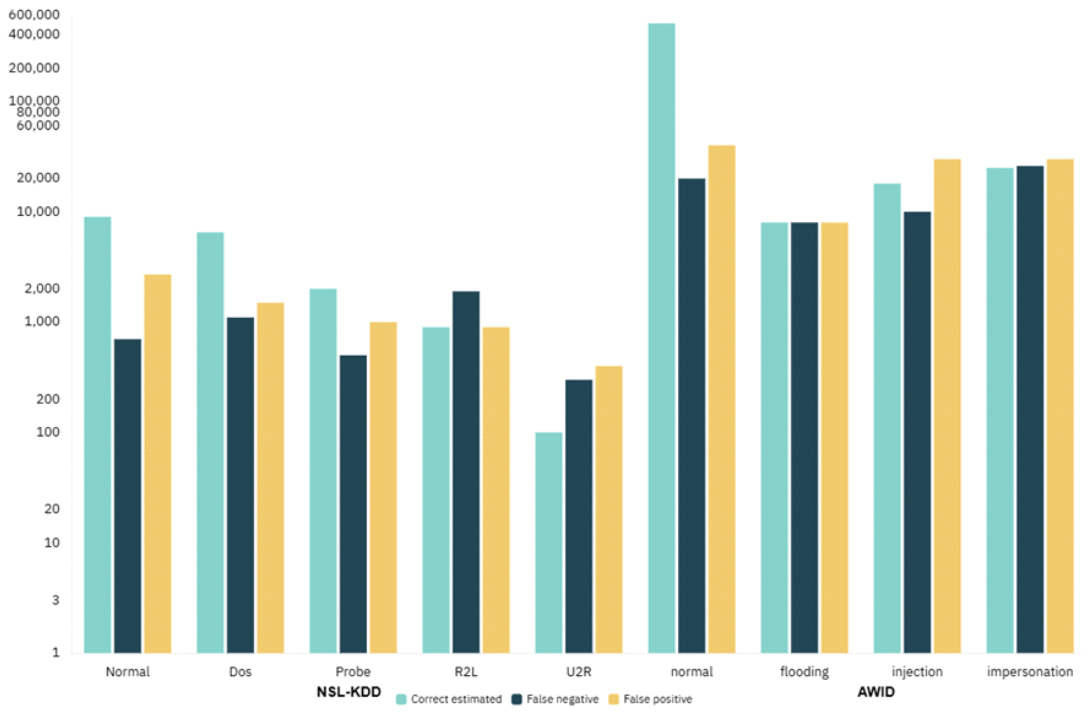

(5)[TeX:] $$\mathscr{L}\left(Q^{\prime}\right)=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=1}^n\left(Y_j-Q^{\prime}\left(S_j, A_j\right)\right)^2$$1. Initialization: In both the environment and classifier agents, the initial values for the Q-functions are randomly assigned. Concurrently, a random initial stste s 0 is chosen from the dataset. The state is subsequently inputted into the Q-function in order to ascertain the optimal action values. It is imperative to emphasize that every state serves as a representative sample from the dataset. 2. Envir onment's Action Selection Pr ocess: The environment determines an action, such as an intrusion label, according to its existing policy and the current state. 3. State Update: Subsequently, the environment randomly picks a state st from the dataset, aligning with the action it has chosen, as represented by S(aet) in Algorithm 1. This process generates the corresponding feature-label pair. 4. Classification by the Agent: Once the state is received from the environment, the classifier agent proceeds to analyze it in accordance with its established policy and subsequently assigns it to a certain action. The procedure described herein exemplifies the conventional operation observed in a typical DQN algorithm. 5. Rewar d Assignment: The selected action, denoted as act , is communicated to the surrounding environment for the purpose of being compared with the ground-truth label. When the classifier’ s prediction aligns with the ground truth, the classifier agent is awarded a positive reward; if not, the positive reward is given to the environment. 6. State Transition: The environment generates a new state as per a standard DQN algorithm. When the agent executes an action, the environment dynamically updates to a new state based on the optimal action values derived from the Q-function. This transition generates the subsequent feature-label pair, representing the network environment’s current state. By incorporating the prevailing policy and action-value function, the system ensures that each state transition accurately reflects the evolving conditions of the network, facilitating precise and adaptive intrusion detection capabilities. 7. Policy Update: In accordance with the DQN update rule, the Q-functions for both the classifier and environment agents are modified by incorporating the reward values and the resultant states. This sequence ensures that both the classifier and the environment agents progressively refine their policies, enhancing the model’s performance in detecting intrusions within the marine tactical network. 3.3.3 Integration with Blockchain for Secure Data Management Data security is paramount in marine tactical networks. By integrating blockchain technology, the system ensures secure and tamper-proof storage of detected intrusions and related data. The decentralized structure of blockchain, coupled with its immutable ledger, provides an additional layer of security, thereby preserving the integrity of the intrusion detection system against potential cyber threats. The blockchain layer interacts with the DQN model by securely recording all significant events, such as detected anomalies and corresponding actions. This ensures that even if parts of the network are compromised, the historical data remains intact and verifiable, thus maintaining the system’s overall security. Ⅳ. Performance AnalysisThe performance analysis section compares the proposed BAE-RL model with a variety of ML and DL models. These assessments were carried out on the selected IDS datasets, NSL-KDD and AWID. 4.1 Selected DatasetsThe proposed model’s effectiveness in intrusion detection is thoroughly evaluated using two well-established datasets within the intrusion detection field: a) NSL-KDD[50] and b) AWID[51]. Those datasets, with their distinct distributions of intrusions and attack types, offer a robust evaluation platform for the model’s performance. Public, labeled MTN traces are scarce; hence, we evaluate on NSL-KDD and AWID as proxystresstestsfor MTN choke points (shipboard Wi-Fi/tactical RF) and backbone segments (ship-shore SATCOM/IP). This choice is explicitly acknowledged as a limitation; however, our adversarial, partially observable training was designed to emulate MTN dynamics (intermittent feedback, evolving adversaries) rather than rely on static signatures. The per-class gains and minority-class behavior supporting MTN use cases are already evident in Table 3 and Fig. 7. Table 3. Performance metrics for NSL-KDD and AWID datasets across attack classes

4.1.1 NSL-KDD Dataset The NSL-KDD dataset remains a benchmark in IDS research, containing 125,973 training and 22,544 test samples with 41 features (38 continuous, 3 categorical). After preprocessing - continuous feature scaling [0-1] and one-hot encoding of categorical attributes - the dataset expands to 122 dimensions. Significant class imbalance exists, with majority classes (43.1%) dwarfing rare attacks (1.7%). The 23 attack labels in training expand to 38 in testing, including 17 novel attack types (16.6% of test samples). Following established practice, attacks are grouped into five categories: Normal, DoS, Probe, R2L, and U2R Fig. 5. 4.1.2 AWID Dataset Designed for IEEE 802.11 network security, the AWID-CLS-R subset contains 2.37M samples (1.8M training, 0.58M test) with 154 features. Post-pre-processing retains 24 critical features after removing null/constant values and network identifiers. The dataset exhibits severe imbalance: 91% normal traffic vs 9% attacks (3.6% injection, 2.7% each flooding/impersonation) as shown in Fig. 5. This challenges model generalization despite comprehensive attack coverage. The adversarial agent demonstrates progressive attack strategy refinement during training Fig. 6. Initial random attacks evolve to targeted patterns: NSL-KDD shows increased “satan”, “ipsweep”, and “warezclient” attacks, while AWID focuses on “flooding” and “impersonation”. This dynamic adaptation counters dataset imbalances and optimizes detection efficacy. The defender employs DQN with experience replay D = 5×105, a target network, and e-greedy exploration decayed 0.1 → 0.01 (Sec. III.3; Eqs. (1)–(5)), which stabilizes TD updates in the adversarial setting (Fig. 4). We stop when the moving-average TD-loss change falls below 10−4 over 10 epochs and the episodic reward plateaus (cf. Fig. 6). Training complexity per epoch is [TeX:] $$\mathscr{O}$$ (EbCf) for episodes E , batch size b , and model cost Cf (LSTM extractor); empirically, our run-time is ∼ 1100 s with prediction ∼ 0. 5-0 . 6 s (Table 4), comparable to deep RL baselines. A compact sensitivity sweep shows that larger γ ∈ {0 . 95, 0. 99} improves minority-class recall at slower convergence, while overly fast decay overfits frequent classes; the adopted schedule preserves the minority-class gains reported in Table 3. Table 4. Prediction and training times for different models

4.2 Performance AssessmentEvaluation metrics reveal critical insights Table 3. Despite dataset imbalances, the model achieves F1 scores of 89.26% (NSL-KDD) and 96.73% (AWID), with precision-recall tradeoffs highlighting effective minority-class detection. F1 emerges as the optimal metric given class distribution challenges, particularly for rare attack types in marine network environments. 4.3 Performance Assessment of NSL-KDD and AWID DatasetsIn this section, the performance of NSL-KDD and AWID datasets is evaluated based on different performance metrics and different detection models. 4.3.1 Different Categories Performance Metrics The results are derived from the test sets detailed in Subsection 4.1.1, and 4.1.2. Because the datasets are highly imbalanced, the performance metrics such as accuracy, F1 score, precision, and recall to evaluate the effectiveness of the models, as shown in Table. 3. The F1 scores of 89.26% and 96.73% for the NSL-KDD and AWID datasets, respectively, underscore the model’s robustness, particularly in handling unbalanced datasets. These scores make F1 the preferred metric for evaluating and ranking the performance of algorithms across both datasets. In multi-class classification, there are two ways to report results: the ‘aggregated’ approach and the ‘one-vs-rest’ approach. The ‘one-vs-rest’ method simplifies the task by treating each class as a binary classification problem, comparing each class against all other classes. On the other hand, ‘aggregated’ results provide a comprehensive summary of classification performance across all classes. Different aggregation techniques, such as micro, macro, samples, and weighted averages, are available, each using a different approach for averaging metrics. In this study, we use the weighted average method provided by scikit-learn to calculate the aggregated F1 score, precision, and recall. Table 3 provides a summary of the aggregated performance metrics for the NSL-KDD and AWID dataset. Considering the constantly changing nature of network traffic, the efficiency of IDS models in terms of prediction and training times is essential. The analysis also encompasses the computation times needed for both the training and prediction phases, as illustrated in Table 4. 4.3.2 Performance for NSL-KDD with Different ML Model The performance evaluation on the NSL-KDD dataset [52], the CNN-1D, demonstrated the highest aggregated F1 score, with the proposed BAE-RL model closely matching its performance. Other models lagged noticeably behind, as depicted in Table 5. This trend is also reflected in the accuracy metrics. While the BAE-RL model’s F1 score was nearly on par with the CNN-1D, its key advantage is the significantly lower computational time required for predictions, as highlighted by the prediction times for all models in Table. 4. Table 5. Performance metrics for NSL-KDD and AWID datasets with different models

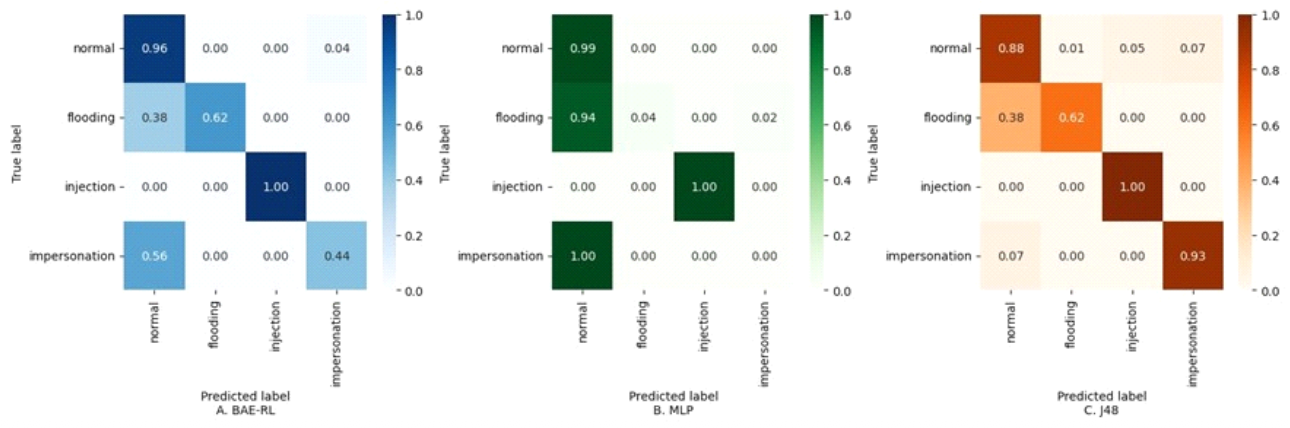

Table. 5 present the accuracy, F1 scores, precision, and recall for various labels when applying the proposed model to the NSL-KDD dataset. The results highlight that the BAE-RL algorithm effectively emphasizes detecting less frequent labels. Although the accuracy remains high across all labels, the influence of false positives is reflected in the F1 scores. The proposed model enhances performance by moderately increasing false positives while substantially reducing false negatives, a critical aspect in the context of IDS. The metrics indicate high F1 values exceeding 79. 4% and accuracy greater than 80. 16% for labels that are not severely imbalanced. The epsilon parameter, which starts near 1 at the beginning of training, gradually decreases to reach the defined lower threshold. The optimal F1 score is achieved when the environment agent’s epsilon parameter is maintained at approximately 80. 16% throughout the training phase. This finding suggests that maintaining a robust level of exploration for the environment agent across the entire training period is crucial for improving classification accuracy. 4.3.3 Performance for AWID with Different ML Models with Confusion Matrix Confusion matrix Fig. 7 illustrates the proposed A) BAE-RL model with two different well-established algorithms, B) MLP and C) J48 used on the AWID dataset [53], which delivered the best classification results as outlined in Table. 5. The proposed model shows the lowest number of false negatives, especially in detecting impersonation and flooding attacks. In comparison, the J48 model, despite achieving high overall accuracy, has a substantial false-negative rate of 94. 79% for impersonation attacks, as indicated in Table 3. Such a high false-negative rate is detrimental to an intrusion detection system, as it implies a significant number of undetected intrusions, which poses a severe risk to network security. The proposed model effectively mitigates this issue by significantly reducing false negatives, thereby providing a more reliable and robust detection system for complex and evolving cyber threats. The BAE-RL model attempts to enhance the classification of under-represented classes, as demonstrated in Fig. 7. The BAE-RL model demonstrates notable efficacy in mitigating false negatives for underrepresented classes. However, this reduction in false negatives comes with a slight increase in false positives for the normal class. Table 5 compares the BAE-RL model’s efficiency metrics on the AWID dataset with other models such as MLP and J48. Although J48 achieves the highest accuracy due to zero false positives in the predominant normal class, it struggles with the rare attack classes, indicating that accuracy alone may not reflect overall performance. The BAE-RL model, with its higher F1 score 96 . 29%, is better suited for imbalanced datasets like AWID, as it provides a more balanced trade-off between precision and recall across all classes, demonstrating enhanced handling of underrepresented scenarios. Notable aspects of model implementation in this study include the adoption of the primal solution for the linear SVM kernel, chosen for its computational efficiency in processing large datasets with a limited feature set. Conversely, the RBF kernel SVM uses the dual approach. The MLP architecture is configured with three hidden layers containing 1024, 512, and 128 neurons, respectively. For the CNN model, a one-dimensional structure is utilized, aligning with the one-dimensional nature of the input feature data. All models, except for the linear SVM, MLP, CNN, and DRL models, were implemented using the scikitlearn package. TensorFlow was employed to implement the linear SVM, MLP, CNN, and DRL models, while BAE-RL was constructed using Tensor-Flow and Keras with a custom dataset sampling code. 4.3.4 Smart Contract Implementation and Validation Smart contract in the proposed framework automate the secure recording and validation of detected threats. This ensures that all intrusion events are logged with accurate metadata, maintaining data integrity and transparency throughout the system [54]. In the proposed BAE-RL model, a critical component is the integration of blockchain technology to ensure the integrity, transparency, and immutability of detected intrusion events. The smart contract was developed using Solidity to automate the process of logging detected threats onto the blockchain. The smart contract is responsible for recording essential metadata, including the timestamp of detection, the type of attack, the system status at the time of detection, and a cryptographic hash of the event, ensuring that all logged data remains secure and tamper-proof. The smart contract was deployed and tested on an Ethereum-based blockchain. Upon the detection of a threat by the BAE-RL model, the event was logged using the logThreat function, which automatically generates and stores a cryptographic hash representing the event data. Fig.8 illustrates the successful execution of this process, where the details of a simulated DDoS attack were securely recorded. The event metadata such as the threat ID (0), timestamp (1725957310), attack type (DDoS), and system status (Under Attack )-was securely logged, and the event hash (0x17ce8f63d7106122...) confirms the immutability of the recorded data. The results validate that the smart contract seamlessly integrates with the BAE-RL system, offering a robust mechanism for storing threat data in an immutable manner. By utilizing cryptographic hashing, the system ensures that no historical data can be altered, thereby fostering trust and providing a transparent audit trail for future verification. This implementation enhances the security framework of the marine tactical network by ensuring that malicious activities, once detected, cannot be erased or manipulated, supporting the system’ s overall goal of improving security and resilience against evolving cyber threats. Ⅴ. ConclusionThe proposed Blockchain-Aided Adversarial Reinforcement Learning (BAE-RL) intrusion detection system exhibits significant improvements in accuracy and robustness compared to existing state-ofthe-art approaches on benchmark intrusion detection datasets. Specifically, BAE-RL achieves weighted accuracy scores of 80.16% on the NSL-KDD dataset and 95.9% on the AWID dataset, outperforming classical machine learning models such as Random Forest (RF) and AdaBoost, which typically achieve accuracies in the mid-70% to low-90% range on these datasets. For example, on NSL-KDD, BAE-RL outperforms CNN-1D models, which achieve approximately 78.75% accuracy, and reinforcement learning baselines, such as Double Deep Q-Networks (DDQN), with 73.72% accuracy. Moreover, BAERL significantly reduces false negatives across underrepresented attack classes, enhancing detection reliability in highly imbalanced scenarios. Its multi-agent adversarial setup fosters adaptability to evolving threats, a key advantage over traditional IDS frameworks reliant on static pattern recognition. Computational efficiency is maintained, with BAE-RL prediction times comparable to leading models (approximately 0.5-0.6 seconds), despite its enhanced complexity. Additionally, the integration of a smart contract provides immutable, tamper-proof logging of detected threats, ensuring secure audit trails without compromising detection speed. Compared to prior blockchain-IDS approaches that report accuracies up to 92.6% but lack real-time adaptability and scalability, BAE-RL balances high detection accuracy with dynamic threat response and secure data integrity, positioning it as a superior, mission-critical solution for marine tactical network cybersecurity. Future research will explore adapting the BAE-RL framework to IoT-enabled industrial control systems and vehicular ad hoc networks, which share similar dynamic topologies and robust security requirements. Multi-agent adversarial learning can dynamically detect evolving threats, while blockchain ensures secure and tamper-proof logging for trust and compliance. Furthermore, integrating federated learning will enable scalable, privacy-preserving training across distributed, heterogeneous nodes, maintaining robustness in large-scale, sensitive environments. BiographyMd Raihan SubhanHe is currently pursuing his Ph.D. degree in the Department of Computer Science with Interdisciplinary Applications while serving as a Graduate Research Assistant at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, USA. He obtained his M.Eng. degree in IT Convergence Engineering from Kumoh National Institute of Technology (KIT), Gumi, South Korea, in 2025, and his B.Sc. degree in Computer Science and Engineering from the International University of Business, Agriculture, and Technology (IUBAT), Bangladesh, in 2018. His research interests include anomaly detection, deep learning, smart contracts, and blockchain applications in logistics. [ORCID:0009-0004-7869-744X] BiographyMd Mahinur AlamHe is pursuing his Master’s in IT Convergence Engineering at Kumoh National Institute of Technology (KIT) in Korea. His Bachelor of Science in Computer Science and Engineering (CSE) from Bangladesh’s International University of Business Agriculture and Technology (IUBAT) was awarded in December 2022. His research interests are Deep Learning, Computer Vision, Federated Learning, and Blockchain. [ORCID:0009-0006-5453-443X] BiographyMohtasin GolamHe received his Ph.D. degree in IT Convergence Engineering from Kumoh National Institute of Technology (KIT), South Korea, in 2025. He received an M.Sc. in IT Convergence Engineering from the same institution. He received his B.Sc. degree in Electrical and Electronics Engineering (EEE) in 2018. He is cur- rently working with the Network System Laboratory (NSL) as a research assistant under the supervision of the ICT Convergence Center. His research interests are Deep learning, Metaverse applications, UAV net- works, IoT, and Blockchain. [ORCID:0000-0001-9784-0679] BiographyMd Facklasur RahamanHe is currently pursuing a Ph.D. from the Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science in the Electronic Systems Engineering depart- ment at the University of Regina and completed his Master’s de- gree in IT Convergence Engineering while working as a full-time researcher at the Networked System Laboratory in Kumoh National Institute of Technology, Gumi, South Korea. He received the B.Sc. degree in electrical and elec- tronic engineering from the Rajshahi University of Engineering and Technology, Bangladesh, in 2016. His research interests include medicine supply chain management, healthcare record management, meta-verse governance and applications, and blockchain. [ORCID:0009-0005-0974-1838] References

|

StatisticsCite this articleIEEE StyleM. R. Subhan, M. M. Alam, M. Golam, M. F. Rahaman, T. Jun, "Blockchain-Aided Intrusion Detection in Marine Tactical Network Using Reinforcement Learning," The Journal of Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences, vol. 50, no. 12, pp. 1937-1957, 2025. DOI: 10.7840/kics.2025.50.12.1937.

ACM Style Md Raihan Subhan, Md Mahinur Alam, Mohtasin Golam, Md Facklasur Rahaman, and Taesoo Jun. 2025. Blockchain-Aided Intrusion Detection in Marine Tactical Network Using Reinforcement Learning. The Journal of Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences, 50, 12, (2025), 1937-1957. DOI: 10.7840/kics.2025.50.12.1937.

KICS Style Md Raihan Subhan, Md Mahinur Alam, Mohtasin Golam, Md Facklasur Rahaman, Taesoo Jun, "Blockchain-Aided Intrusion Detection in Marine Tactical Network Using Reinforcement Learning," The Journal of Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences, vol. 50, no. 12, pp. 1937-1957, 12. 2025. (https://doi.org/10.7840/kics.2025.50.12.1937)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||